Table of Contents

Security in embedded systems is not a feature; it’s a foundational business requirement for managing operational, financial, and reputational risk. For connected devices deployed in medical, industrial, or aerospace contexts, a security failure can have catastrophic real-world consequences. A proactive, secure-by-design approach is the only effective defense against these threats.

The Unseen Risks Lurking in Connected Devices

The proliferation of connected devices has created a vast and often undefended attack surface. Unlike enterprise IT environments, embedded systems operate under unique constraints that invalidate traditional security models. These devices are frequently deployed in physically accessible locations and are expected to operate reliably for years, sometimes decades, far beyond typical IT hardware lifecycles. This extended operational window dramatically increases risk, as vulnerabilities discovered years after deployment can become latent threats if the device cannot be securely patched in the field.

Why Traditional IT Security Fails

Applying standard IT security practices to embedded systems is ineffective due to fundamental differences in their operating environment and resource constraints.

- Resource Constraints: Most embedded systems operate with minimal processing power, memory, and power budgets. Resource-intensive solutions like antivirus software or complex stateful firewalls are typically not viable.

- Long Lifecycles: An industrial controller or medical implant may have an operational requirement of 15+ years, far outlasting a typical server’s refresh cycle. Security must be sustainable for the device’s entire lifespan.

- Physical Access: Many embedded devices are physically exposed, introducing attack vectors that are non-issues in a secured data center. JTAG debug ports, UART consoles, and direct memory access interfaces can provide a direct path for attackers to compromise a system.

The most critical point of failure is treating security as a feature to be added late in the development cycle. Architectural security flaws discovered after deployment are often impossible to remediate without a full product recall and redesign—a scenario that entails massive costs, regulatory penalties, and irreparable brand damage.

Quantifying the Business Impact

The growth of the embedded security market underscores the increasing urgency. Valued at US$7,163.4 million in 2025, the global market is projected to reach US$10,420.4 million by 2032, expanding at a 5.5% CAGR, according to embedded security market projections on Persistence Market Research.

A breach in an embedded system is not merely a data leak; it can trigger severe real-world consequences, creating direct business liabilities. These include operational downtime in a manufacturing facility due to a compromised PLC, patient harm from an incorrect dosage delivered by a hacked medical device, or loss of vehicle control in an automotive system. These are not abstract risks; they are tangible failures that impact revenue, attract regulatory scrutiny, and erode customer trust.

Pragmatic Threat Modeling for Real-World Systems

Threat modeling for embedded systems must be a pragmatic engineering discipline, not an academic exercise. Its purpose is to identify credible threats early in the design cycle when mitigation is least costly. Waiting until the prototype stage to consider security introduces significant project risk, leading to expensive rework and schedule delays. The core problem threat modeling solves is the misallocation of resources; without a structured process, teams often over-engineer defenses for improbable scenarios while missing simple, high-impact vulnerabilities.

A Lightweight Approach for Embedded Hardware

For resource-constrained systems, a tailored threat modeling framework like STRIDE is highly effective. STRIDE (Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, Elevation of Privilege) provides a structured lens to analyze hardware-specific attack surfaces and translate abstract risks into concrete engineering requirements.

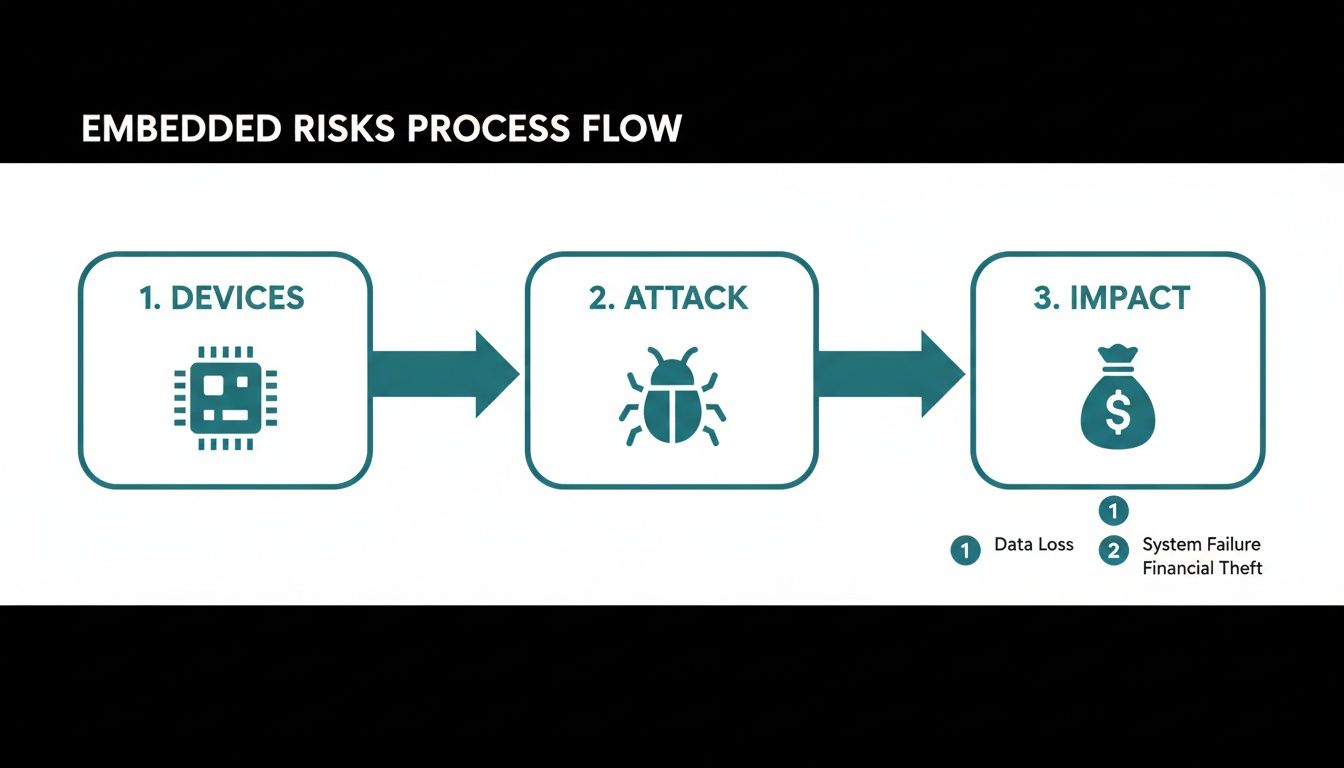

The objective is to map a potential attack path from the initial exploit to the ultimate business impact.

This analysis makes it clear how a vulnerability in hardware or firmware can directly translate into data loss, financial theft, or operational failure.

Real-World Scenario: A Connected Infusion Pump

Consider the development of a network-connected medical infusion pump, where a security failure can directly impact patient safety.

Problem: The device must receive dosage instructions via Wi-Fi and permit maintenance updates through a physical USB port. These represent multiple entry points for an attacker.

Diagnosis: Applying a focused STRIDE model identifies the most critical threats. An attacker could tamper with firmware via the USB port to alter dosage limits (Tampering). They could intercept unencrypted Wi-Fi traffic to access protected health information (Information Disclosure). Or they could launch a flood of network packets to crash the device, halting treatment (Denial of Service).

Solution: The threat model directly generates specific, actionable security requirements. A secure boot process is mandated to block unauthorized firmware. TLS encryption is required for all network communications. The USB port must be architected to accept only cryptographically signed update packages.

Outcome: The engineering team receives a prioritized list of security controls directly tied to mitigating credible patient safety and data privacy risks. This prevents wasted effort on low-probability threats and aligns development with core business and regulatory obligations. In regulated environments, a deep understanding of standards like ISO 14971 for medical device risk management is non-negotiable.

At its core, threat modeling is a risk management activity. Its primary output is not a list of features, but a shared understanding of which risks are acceptable and which must be mitigated, directly informing budget, schedule, and engineering priorities.

The right framework depends on the project’s scale and risk profile.

Threat Modeling Frameworks for Embedded Applications

| Framework | Primary Focus | Best Suited For | Key Tradeoff |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRIDE | Identifying threat categories across software and system components. | General-purpose software and complex systems where a broad threat overview is needed. | Can feel too abstract for hardware-specific issues without deliberate adaptation. |

| PASTA | Attacker-centric, aligning business objectives with technical risks. | High-value systems in regulated industries (e.g., finance, healthcare) requiring compliance evidence. | Process-intensive; can be overkill for smaller, less critical embedded projects. |

| DREAD | Risk-rating threats based on Damage, Reproducibility, Exploitability, Affected users, Discoverability. | Prioritizing a known list of vulnerabilities to focus remediation efforts effectively. | Less effective for discovering new threats; it’s primarily a prioritization tool. |

| Hardware Triage | Physical interfaces, side-channel attacks, and supply chain integrity. | Devices with high physical exposure (e.g., IoT sensors, industrial controllers). | May overlook network or application-layer vulnerabilities if used in isolation. |

The goal is not to find a “perfect” framework, but to select one that facilitates a structured conversation about security. Even a lightweight, informal process is infinitely better than no process at all.

Building a Hardware-Anchored Root of Trust

Effective security cannot be implemented in software alone; it must be anchored in the silicon itself. A hardware-anchored root of trust (RoT) is the immutable foundation upon which all other security layers are built. Without it, the integrity of the system cannot be reliably verified.

The fundamental problem is that software is mutable. If an attacker can modify the initial boot code, they gain control of the entire system and can bypass any software-based security controls. This renders even the most robust application-level security measures useless. The only viable solution is to establish a secure boot chain—a cryptographic process where each stage of the boot-up sequence verifies the integrity of the next, starting from a component that cannot be altered.

The Secure Boot Process Unpacked

A secure boot sequence creates an unbroken “chain of trust,” originating from an immutable primary bootloader stored in Read-Only Memory (ROM) on the microcontroller or System-on-Chip (SoC). This code is fused during manufacturing, making it the first, unalterable link in the chain.

- Immutable Boot ROM: On power-on, the processor executes this unchangeable code from the boot ROM.

- Signature Verification: This code loads the next-stage bootloader (e.g., from flash memory) and uses a public key—stored in immutable, one-time-programmable hardware—to verify its cryptographic signature.

- Chain Loading: If the signature is valid, control is transferred to the now-trusted second-stage bootloader. This verification process repeats for each subsequent stage, including the operating system kernel and application code.

If any signature verification fails, the boot process is halted. This mechanism ensures the device will only execute authentic, unmodified firmware, effectively locking out unauthorized code from the first instruction cycle.

Choosing Your Hardware Anchor: The Critical Tradeoffs

Implementing a hardware RoT is a critical architectural decision made early in the design process. The choice between a discrete security component and an integrated solution has significant implications for cost, PCB footprint, and design complexity. Making the right decision requires balancing the product’s risk profile against its business constraints—a process where specialized hardware engineering services can provide critical guidance.

A hardware root of trust does not make a system “unhackable.” It ensures that if a compromise occurs, the system can reliably detect that it is in an unauthorized state and force a revert to a known-good configuration on the next reboot. This containment capability is the essence of device resilience.

The following table outlines the key decision factors between discrete and integrated RoT solutions.

| Factor | Discrete Trusted Platform Module (TPM) | Integrated MCU/SoC Security Features |

|---|---|---|

| Security Level | Highest; often certified to standards like FIPS 140-2 or Common Criteria. Provides robust tamper resistance. | Varies by vendor; offers strong protection but may lack formal certifications required for some regulated markets. |

| Cost | Adds a discrete component to the Bill of Materials (BOM), increasing per-unit cost. | Integrated into the primary MCU/SoC, generally offering a lower BOM cost for the security functionality. |

| Board Space | Requires additional physical space on the PCB, a critical constraint for highly miniaturized devices. | No additional footprint, as security peripherals are part of the main chip. |

| Implementation | Can involve more complex integration with the host processor and software stack. | Often comes with vendor-provided libraries and tools, potentially simplifying the development and integration effort. |

For a consumer IoT device, an MCU with integrated hardware cryptographic accelerators and a secure boot ROM may offer the optimal balance of security and cost. For a medical device or aerospace controller, where failure is not an option, the certified assurance provided by a discrete TPM is often the only responsible choice. Validating these implementations is also crucial, which is why automating testing for secure hardware systems is a key part of the process.

Securing Firmware and Over-the-Air Updates

A device’s security posture is not static; it must be maintained throughout its operational lifecycle. For embedded systems, this lifecycle can span a decade or more, leaving them exposed to new exploits discovered long after shipment. Any device that cannot be securely updated in the field is a latent liability.

The absence of a robust and secure Over-the-Air (OTA) update mechanism is a critical architectural failure. Without it, patching a security flaw requires expensive and logistically complex physical interventions or a full product recall. A secure OTA system is a non-negotiable requirement for managing long-term risk and maintaining product viability.

Architecture of a Resilient OTA Update System

A secure OTA process is more than a simple file transfer; it is an orchestrated sequence of cryptographic checks designed to ensure that only legitimate, untampered firmware can be installed, even over an unreliable or hostile network.

A resilient system requires several key architectural components:

- Cryptographically Signed Firmware: Every update package must be digitally signed using a private key held securely by the manufacturer. The device stores the corresponding public key and will reject any firmware that lacks a valid signature. This is the primary defense against the installation of malicious code.

- Encrypted Delivery Channel: While the signature protects firmware integrity, the update must be delivered over an encrypted channel (e.g., TLS) to protect its confidentiality. This prevents attackers from reverse-engineering the software via network eavesdropping.

- Anti-Rollback Protection: A common attack vector is to downgrade a device to an older firmware version with known vulnerabilities. A secure OTA mechanism prevents this by storing the current version number in secure, non-volatile memory and rejecting any update with a lower version number.

- Power-Fail-Safe Recovery: The device must recover gracefully from a power loss during an update to avoid being “bricked.” This is typically handled with an A/B partition scheme: the new firmware is written to an inactive partition, and only after it is fully downloaded and verified does the bootloader switch to the new partition, retaining the previous version as a fallback.

Implementing this correctly requires deep expertise in embedded constraints, which is why many teams engage specialized firmware engineering services.

A secure OTA mechanism transforms a static, depreciating asset into a dynamic, adaptable platform. It’s the difference between a product that becomes obsolete the moment a vulnerability is found and one that can be hardened and improved over its entire service life.

Use Case: Automotive OTA Updates

The automotive sector provides a compelling example of the business impact of OTA updates. The market for embedded automotive security, valued at $5.60 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $8.90 billion by 2032 at a 5.96% CAGR, driven largely by connected vehicle technology according to the growth of the embedded security market on 360iResearch. The 2015 remote compromise of a Jeep Cherokee, which exposed 1.4 million vehicles to remote takeover, highlighted the catastrophic potential of unpatched vulnerabilities.

Let’s analyze that scenario:

- Problem: A critical vulnerability is discovered in the Engine Control Unit (ECU) software of a vehicle model already in the field. Without OTA capabilities, the only remedy is a massive and costly recall requiring owners to visit a dealership for a manual software update.

- Diagnosis: The absence of a secure remote update mechanism rendered the entire vehicle fleet a static target, unable to adapt to an emerging threat.

- Solution: With a secure OTA system, the manufacturer can push a signed and encrypted patch directly to all affected vehicles. The vehicle downloads the update, verifies its authenticity, and applies it during the next ignition cycle.

- Outcome: The vulnerability is remediated across the fleet in days, not months. The manufacturer avoids a multi-million-dollar recall, protects customers from a severe safety risk, and demonstrates a commitment to security that builds long-term brand trust.

Validating Security Through Rigorous Testing

A secure-by-design philosophy is necessary but not sufficient; security assumptions must be validated through rigorous, adversarial testing. A common failure is confusing functional validation with security validation. A device can pass all quality assurance checks and still contain critical vulnerabilities that standard functional tests will never detect.

The diagnosis is a gap in testing methodology. Standard QA asks, “Does this feature work as specified?” Security testing asks, “How can I make this feature behave in an unexpected way that compromises the system?” This requires a shift in mindset and a specialized toolkit designed to probe for weaknesses, not just confirm correct operation. The solution is a multi-layered security validation plan that actively attempts to break the system.

Core Methodologies for Security Validation

A comprehensive testing strategy should incorporate several methodologies targeting different layers of the system.

Static Analysis (SAST): SAST tools automatically scan source code for common vulnerabilities like buffer overflows, integer overflows, and improper use of cryptographic APIs. Integrating SAST into a CI/CD pipeline provides immediate feedback to developers, catching potential issues before they are compiled.

Dynamic Analysis (DAST): DAST tools probe the running system’s external interfaces (e.g., network sockets, serial ports) with malformed or unexpected data to identify crashes or error conditions that may indicate underlying vulnerabilities.

Penetration Testing: This simulates a real-world attack. For embedded systems, this extends beyond network scans to include probing physical hardware interfaces like JTAG and UART to gain memory access or a root shell. It also involves attacking wireless protocols like Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) or Zigbee to attempt device spoofing or data interception.

The goal of security validation is not to achieve a perfect score on a report but to discover hidden risks before an attacker does. Every vulnerability found in the lab is a potential crisis averted in the field. This proactive discovery is a direct investment in risk reduction.

Real-World Scenario: Fault Injection on a Smart Lock

Consider the security validation of a new battery-powered smart lock.

- Problem: A new smart lock has passed all functional tests—it unlocks with the correct digital key and remains locked otherwise. However, the security validation plan focused solely on software and network protocols.

- Diagnosis: The test plan overlooked the threat of physical, non-invasive attacks. An attacker could employ fault injection (or “glitching”) by briefly disrupting the microcontroller’s power supply during a critical operation, such as credential validation.

- Attack: A penetration tester executes a voltage glitching attack. By inducing a momentary voltage drop at the precise moment the MCU is verifying a key’s cryptographic signature, they cause the processor to skip a crucial instruction.

- Outcome: The

if (signature_is_valid)check fails to execute correctly, and the lock’s control flow mistakenly branches to the “unlock” routine, opening the door without a valid key. This failure mode was invisible to standard software testing and reveals a critical hardware vulnerability that requires architectural changes to mitigate, such as adding brown-out detection circuitry.

In regulated industries, this level of validation is often mandatory. Standards like IEC 62304 (medical devices) and DO-178C (avionics) require documented evidence of rigorous verification and validation activities that explicitly address security risks.

Your Action Plan for Embedded Systems Security

Effective embedded security is a discipline, not a one-off project. It must be integrated into your engineering culture to deliver reliable, scalable, and defensible products. Security should be framed as a strategic advantage that reduces risk and builds customer trust, not as a cost center.

A Pragmatic Checklist for Business Impact

This focused, three-point action plan ties security investments directly to tangible business outcomes, facilitating buy-in across engineering and executive teams.

Risk Reduction: Before your next project kickoff, conduct a formal threat modeling workshop. This is the single highest-leverage activity for instilling a security-first mindset. Its output—a prioritized list of credible threats—will guide the entire development process, ensuring resources are focused on the most probable and impactful risks.

Speed to Market: Integrate automated security testing (SAST) into your CI/CD pipeline from day one. Identifying vulnerabilities early in the development cycle is exponentially cheaper and faster to fix than discovering them pre-release. This transforms security from a late-stage bottleneck into an accelerator for delivering robust products on schedule.

Cost Control: During the initial architecture phase, mandate a formal decision on your hardware root of trust. Selecting the appropriate level of hardware security—whether an integrated MCU feature or a discrete TPM—is a critical business decision that directly impacts your bill of materials. This prevents both the liability of under-engineering and the unnecessary expense of over-engineering.

Adopting this mindset transforms security from a reactive, compliance-driven task into a proactive driver of product quality and resilience. A secure product is inherently more reliable, builds customer trust, and creates a durable competitive advantage.

Implementing these measures requires both strategic vision and deep technical expertise. For teams looking to build this capability efficiently, expert embedded software development services can provide the focused experience needed to establish a strong security foundation.

Common Questions from the Trenches

Here are common questions from engineering leads and product owners, with straightforward, actionable answers.

“We Have Limited Security Expertise. Where Do We Even Start?”

Your highest-leverage first step is threat modeling, conducted at the very beginning of the design phase. This is not about deep cryptographic knowledge; it is about shifting your team’s mindset to consider adversarial thinking before a single line of code is written.

Gather the team and brainstorm potential threats using a simple framework like STRIDE, focusing on system-level risks. Identify your “crown jewels”—the most critical assets—and the most likely ways an attacker might target them. This process ensures your limited resources are aimed at the vulnerabilities that matter most. An external consultant can help jumpstart this process and identify common blind spots.

“What’s the Single Biggest Security Mistake You See Teams Make?”

The most common and costly mistake is treating security as a feature to be added late in the development cycle. This approach is rarely successful and leads to significant delays and budget overruns.

When security is not integrated from the start, foundational architectural decisions—such as MCU selection, memory layout, and the boot process—can make it impossible to implement robust protections later without extensive re-engineering.

Security must be an integral part of the architecture, not a final checkbox. Attempting to add it later is like trying to add a foundation to a house that has already been built. It is expensive, disruptive, and the final result will never be as sound.

“How Do We Balance Security With Performance and Cost?”

This is the central engineering tradeoff in embedded systems. The key is to make risk-informed decisions based on a clear understanding of your application’s specific threat model.

Not every device requires the security of a flight controller or a pacemaker. Your threat model should dictate the necessary controls.

- For a low-cost consumer IoT device, an MCU with basic hardware crypto and a secure boot ROM might be sufficient.

- For a high-risk industrial control system, a dedicated Trusted Platform Module (TPM) or secure element may be non-negotiable to meet security and regulatory requirements.

The goal is not absolute security, but an appropriate level of security that mitigates the most probable and impactful threats for your product’s specific cost and performance envelope. This pragmatic approach avoids both dangerous under-engineering and wasteful over-engineering.

Building secure, reliable, and defensible embedded systems requires a blend of strategic foresight and deep technical expertise. At Sheridan Technologies, we help teams navigate these complexities from architecture to production.

To ensure your next project is built on a solid security foundation, start with a focused security architecture review. Contact Sheridan Technologies for an expert assessment or technical consultation.