Table of Contents

Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DFMA) is not an academic exercise; it is a strategic engineering discipline for de-risking product launches and controlling lifecycle costs. It moves critical production planning from a late-stage gate review to the core of the initial design process.

At its heart, DFMA is a methodology focused on two operational objectives: designing components for efficient manufacturing and designing the final product for simple, error-proof assembly. The goal is to reduce costs, increase reliability, and accelerate time-to-market by addressing the realities of production from day one. This is not a final quality check; it is a concurrent engineering strategy woven into the entire product development lifecycle.

From Siloed Engineering to Strategic Advantage

The classic “over-the-wall” engineering workflow is a primary driver of budget overruns, schedule delays, and late-stage redesigns. In this failed model, the engineering team develops a design optimized for performance specifications in isolation, then delivers it to the manufacturing team, triggering a collision with physical and financial reality.

This sequential process guarantees friction. It produces overly complex parts that are difficult to machine, assemblies requiring custom tooling, or tolerance stack-ups that result in high scrap rates. The operational symptoms are predictable: supplier pushback on feasibility, a flood of late-stage Engineering Change Orders (ECOs), and a product launch that misses its critical market window.

Adopting a Proactive DFMA Framework

The solution is to replace sequential workflows with concurrent engineering. Design for manufacture and assembly must be a cross-functional discipline from project inception, integrating manufacturing and supply chain expertise into the earliest concept stages—long before designs are committed to CAD.

This shift systematically de-risks the production process, delivering measurable business impact:

- Cost Control: A significant majority—often cited as 70-80%—of a product’s lifecycle costs are locked in during the design phase. Addressing manufacturability issues early prevents the compounding cost overruns associated with late-stage changes.

- Risk Reduction: Early collaboration with manufacturing partners identifies and mitigates potential production bottlenecks, material sourcing constraints, and quality control challenges before they can derail the project timeline.

- Speed to Market: A design optimized for production moves through prototyping, validation, and full-scale manufacturing with fewer iterations and delays, creating a more predictable path to revenue.

By treating manufacturability as a primary design constraint—equal in importance to performance and features—companies transform DFMA from a technical checklist into a powerful engine for building a durable competitive advantage.

The Core Principles of High-Impact DFMA

Effective DFMA is a quantitative engineering discipline built on specific, measurable principles. For engineering and operations leaders, these principles provide a clear framework for challenging designs, identifying inefficiencies before they reach the production line, and driving tangible financial results.

These principles represent the most critical levers for reducing cost and accelerating market entry. DFMA embodies the philosophy of continuous improvement in manufacturing—an iterative process of optimizing both the product design and the production process.

Principle 1: Ruthlessly Minimize Part Count

Problem: A design review reveals an excessive number of individual components, fasteners, brackets, and connectors. Each part introduces costs for purchasing, inventory, quality inspection, and assembly labor.

Diagnosis: A high part count is a direct driver of cost and complexity. It inflates the Bill of Materials (BOM), complicates supply chain management, and increases the probability of assembly error. Every additional component is another potential point of failure.

Solution: Aggressively challenge the existence of every component using a structured analysis. For each part, ask three critical questions based on the original Boothroyd Dewhurst methodology:

- Does the part move relative to adjacent parts during normal operation?

- Must it be made of a different material due to fundamental physical properties?

- Must it be separate to allow for assembly, disassembly, or service?

If the answer to all three is “no,” the part is a primary candidate for elimination or consolidation. This forces engineers to integrate functions, often replacing multiple simple components with a single, more intelligently designed part (e.g., via molding or advanced machining), which radically simplifies the assembly process and often improves structural integrity.

Principle 2: Standardize Components and Features

Problem: A design contains a chaotic mix of unique components across a single product or product family. For example, a device may use multiple screw types and sizes where a single, common fastener would suffice.

Diagnosis: Lack of standardization imposes a significant, unnecessary operational tax. It complicates procurement with excess SKUs, inflates inventory holding costs, and introduces a high risk of operator error on the factory floor.

Solution: Implement a strategic standardization program.

- Establish a preferred parts library: Mandate the use of pre-vetted, common components (fasteners, connectors, sensors) unless a deviation is technically justified and formally approved.

- Design modular platforms: Utilize common sub-assemblies or modules across multiple product variants to achieve economies of scale in purchasing and production.

- Leverage symmetry: Where possible, design symmetrical parts that can be installed in multiple orientations or on opposite sides of an assembly, reducing the number of unique part numbers to manage.

The business impact includes lower inventory costs, improved pricing through bulk purchasing, and simplified assembly instructions that reduce error rates.

Principle 3: Design for Foolproof Assembly (Poka-Yoke)

Problem: A product can be assembled incorrectly, leading to failed quality checks, expensive rework, or field failures that trigger warranty claims and damage brand reputation.

Diagnosis: The design lacks features that physically prevent incorrect assembly. Relying solely on operator skill and attention introduces unacceptable quality risk, particularly in high-volume production environments. This principle is often called Poka-yoke, a Japanese term for mistake-proofing.

Solution: Intentionally design components that can only be assembled in the correct orientation.

- Asymmetrical features: Add non-functional lugs, notches, or varied hole patterns that ensure a part fits only one way.

- Self-aligning features: Incorporate chamfers, guides, and lead-in features that naturally guide components into their correct positions.

- Keyed connectors: Use physically distinct connectors for power, data, and I/O to make it impossible to mis-mate cables and damage electronics.

The outcome is a significant reduction in assembly errors, a higher first-pass yield, and a more reliable product—a non-negotiable requirement in regulated industries.

Principle 4: Implement Functional Tolerancing

Problem: Engineers specify excessively tight tolerances on non-critical features, driving up manufacturing costs without adding functional value.

Diagnosis: This common pitfall stems from a “better safe than sorry” design mentality. However, every tightened tolerance has a direct cost implication, often requiring more precise machinery, slower cycle times, increased inspection, and higher scrap rates.

Solution: Conduct a thorough tolerance stack-up analysis to identify which dimensions are truly critical to product function and which are not. For all non-critical features, specify the loosest possible tolerance that maintains performance requirements.

This practical approach can slash component costs and increase manufacturing yield without compromising quality. Foundational work by Boothroyd Dewhurst on a Xerox machine redesign, for instance, cut part count by 41%, leading to manufacturing cost savings of around 45%. You can explore more of these foundational case studies on the DFMA website.

Integrating DFMA into the Product Development Lifecycle

Effective Design for Manufacture and Assembly is not a final checklist; it is a discipline integrated into every stage of the product development lifecycle. Treating DFMA as an afterthought guarantees budget overruns and schedule delays.

A structured, phased approach makes manufacturability a shared responsibility across mechanical, hardware, and supply chain teams. It prevents the common scenario of discovering a critical, unfixable flaw immediately after design freeze. By integrating DFMA from day one, it becomes a proactive strategy for risk mitigation, not a reactive exercise in damage control.

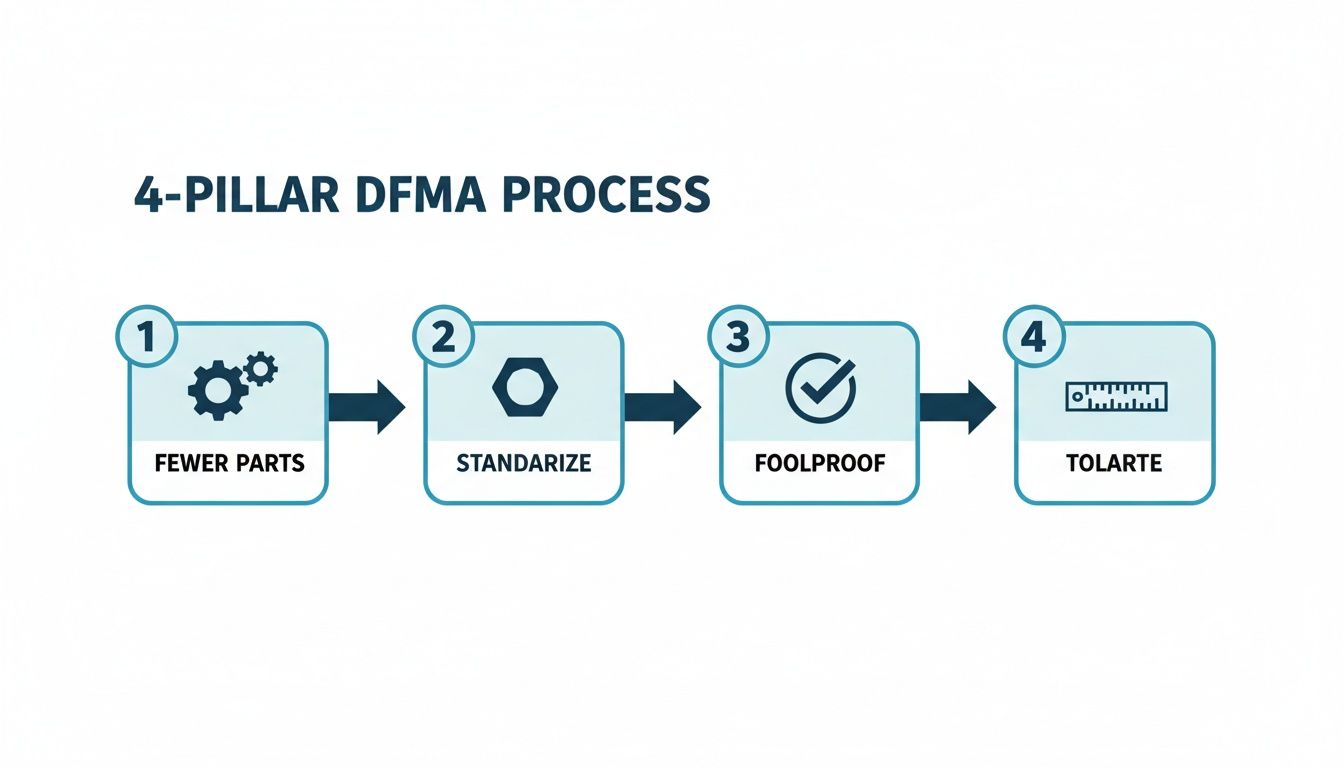

The process is built on four foundational pillars: minimizing part count, standardizing components, mistake-proofing assembly, and optimizing tolerances.

This flow is a roadmap for creating a robust, cost-effective, and reliable product design ready for scalable production.

Phase 1: Concept and Architecture

This is the point of maximum leverage. Decisions made here regarding materials, core architecture, and manufacturing processes have an outsized impact on final product cost and scalability.

- Key Activity: High-level evaluation of manufacturing processes (e.g., injection molding vs. CNC machining) and material selection based on tooling cost, cycle times, and supply chain stability—not just performance specifications.

- Primary Objective: Establish a foundational “manufacturing playbook” that aligns technical requirements with business goals, including preliminary cost models to forecast the financial impact of architectural decisions.

- Tradeoff: A high-performance material may offer a competitive edge but require a specialized, high-cost manufacturing process or rely on a fragile supply chain. Engineering and supply chain teams must collaborate to balance technical ambition with operational reality.

Ignoring DFMA at this stage is the single most common and costly mistake, locking in assumptions that become exponentially more expensive to change later.

Phase 2: Detailed Design

As the design solidifies in CAD, DFMA analysis becomes more granular and quantitative. Core principles of part consolidation and standardization are applied with rigor.

- Key Activity: Formal tolerance stack-up analysis and the use of CAD-based manufacturability checks. Engineers must analyze how individual component tolerances accumulate across an assembly to identify potential interference issues before committing to fabrication.

- Primary Objective: Refine part geometry for the chosen manufacturing process (e.g., adding draft angles for molding) and simplify assembly sequences (e.g., designing for tool-less assembly, standardizing fasteners).

- Constraint: Architectural decisions from Phase 1 establish the guardrails. The goal is to optimize within that framework. The challenge is ensuring that geometric refinements do not compromise the product’s core functional requirements.

The global electronics contract manufacturing market, which was valued at $1.45 trillion as of 2021, is heavily influenced by DFMA principles. The methodology, pioneered in the 1970s and 80s, gained prominence when early studies demonstrated its ability to reduce development costs by 30-50% through disciplined part-count reduction and assembly optimization.

Phase 3: Prototyping and Validation

Prototyping is not just a functional check; it is a critical DFMA validation tool. Physical parts provide invaluable, tangible feedback on the assembly process.

- Key Activity: Time-and-motion studies of physical assembly trials. Have technicians build prototypes against a stopwatch to identify ergonomic challenges, difficult-to-handle components, or ambiguous assembly steps.

- Primary Objective: Validate assembly instructions and identify unforeseen physical constraints before committing to six-figure production tooling. This is the last opportunity to correct expensive mistakes cheaply.

- Failure Mode: The “hero” prototype—a one-off build that functions perfectly but is impossible to replicate at scale. A successful prototype must also validate that the assembly process itself is viable for production volumes. Our approach to hardware engineering services emphasizes creating prototypes that are true pathfinders for mass production.

Phase 4: Supplier Selection and Production Ramp-Up

Engaging with Contract Manufacturers (CMs) and suppliers should not wait until the design is “final.” Their deep, process-specific expertise is a vital DFMA resource.

- Key Activity: Early supplier engagement under NDA. Share preliminary designs with potential manufacturing partners to get direct feedback on process capabilities, tooling strategies, and potential cost drivers.

- Primary Objective: Align the design with the specific capabilities of your chosen manufacturing partner to minimize the risk of late-stage changes. Understanding the essential 5 steps to initiating manufacturing for your product is key to a smooth handoff.

- Risk: Selecting a supplier based solely on the lowest piece-part price without evaluating their engineering collaboration is a critical error. A partner providing meaningful DFMA feedback is exponentially more valuable than one who blindly executes a flawed design.

This table summarizes how DFMA principles are a continuous thread throughout product development, with specific objectives and risks at each stage.

DFMA Integration Across Product Development Stages

| Development Stage | Key DFMA Activity | Primary Objective | Common Pitfall to Mitigate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept & Architecture | High-level process/material evaluation, initial cost modeling. | Establish a cost-effective manufacturing “playbook” aligned with business goals. | Locking in expensive materials or processes that are hard to change later. |

| Detailed Design | Part consolidation, standardization, tolerance analysis. | Refine geometry for specific processes and simplify assembly sequences. | Optimizing a part in isolation without considering its impact on the total assembly. |

| Prototyping & Validation | Physical assembly trials, ergonomic testing, instruction validation. | Confirm the assembly process is viable and efficient before tooling investment. | Creating a “hero” prototype that works but cannot be manufactured at scale. |

| Supplier & Production | Early engagement with CMs for feedback on tooling and processes. | Align the final design with the manufacturer’s actual capabilities and constraints. | Selecting a supplier on price alone, ignoring their collaborative engineering value. |

By proactively addressing these activities and pitfalls at each stage, teams can ensure that manufacturability is a core component of the design, not an expensive problem to be solved at the finish line.

Real-World DFMA Scenarios and Business Outcomes

Theoretical principles are only valuable when applied to solve complex engineering challenges. The following scenarios illustrate how a disciplined DFMA mindset translates directly into lower costs, improved serviceability, and superior product performance.

The global electronics contract manufacturing market, which reached USD 515.1 billion in 2022 and is projected to grow at a 9.7% CAGR (2023-2030), is powered by experts in manufacturability. Data from Grand View Research and other industry analyses consistently show that a robust DFMA process can reduce assembly costs by 20-50%, a decisive competitive advantage.

Case 1: Medical Device Assembly Costs and Reliability

Problem: A medical device startup’s innovative handheld diagnostic tool was functional but prohibitively expensive to build. High assembly costs and inconsistent performance threatened the product’s launch and financial viability.

Diagnosis: A teardown analysis revealed two primary issues. First, the design relied on an excessive number of small, custom fasteners, requiring slow, error-prone manual handling and torquing. Second, an incomplete tolerance analysis resulted in excessively tight specifications for the injection-molded housings, causing a high scrap rate.

Solution: The team initiated a targeted redesign with clear DFMA objectives.

- Fastener Consolidation: The majority of screws were eliminated and replaced with integrated snap-fit clips and interlocking features designed directly into the housing molds.

- Self-Alignment: Key components like the main PCB and sensor module were redesigned with self-aligning posts and channels, making incorrect installation physically impossible.

- Tolerance Relaxation: A formal tolerance analysis identified non-critical dimensions, allowing for looser specifications that dramatically improved the manufacturing yield of molded parts without impacting function.

Outcome: The redesigned product achieved a 40% reduction in final assembly time. The mistake-proofed assembly process also significantly increased device consistency and reliability, streamlining the path toward regulatory validation.

Case 2: Industrial Automation Field Serviceability

Problem: An established industrial automation company faced customer complaints regarding a legacy control panel. While reliable in operation, field servicing was a time-consuming process, leading to extended customer downtime and high service costs.

Diagnosis: The root cause was a monolithic, non-modular design. Accessing internal components like a power supply or I/O card required extensive disassembly of the enclosure, complicated by a dense, point-to-point wired harness.

Solution: The next-generation design mandated field serviceability as a primary requirement.

- Modular Architecture: The system was re-architected into field-replaceable units (FRUs). The power supply and I/O blocks were designed as self-contained modules that could be swapped individually.

- Tool-less Access: High-wear components were placed behind hinged panels secured with quarter-turn fasteners, eliminating dozens of screws.

- Simplified Connectivity: Internal wiring was converted to keyed, quick-disconnect connectors, eliminating the risk of miswiring during field repairs.

Explore similar design objectives in our work within the industrial automation space.

Outcome: The redesigned panel reduced the Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) by 60%. This not only generated significant service cost savings but also became a key competitive differentiator, offering customers reduced downtime and a lower total cost of ownership.

Case 3: Aerospace Weight and Part Count Reduction

Problem: An aerospace client needed to reduce the weight and complexity of a UAV sensor pod. The existing design, an assembly of multiple machined aluminum parts, was overweight and had an excessively long assembly time.

Diagnosis: The design was constrained by conventional manufacturing assumptions. The multi-part construction necessitated dozens of fasteners, brackets, and seals, each adding weight and introducing potential failure points.

Solution: The engineering team pivoted to an additive manufacturing approach. Using topology optimization software, they designed a single, organic structure that consolidated the function of over a dozen separate components. This complex, lightweight part was then 3D printed from a high-strength, aerospace-grade polymer.

Outcome: The additively manufactured pod eliminated 75% of the total part count and reduced the assembly’s weight by 30%. For the UAV, this weight saving directly translated to increased flight duration and payload capacity—a critical performance advantage.

Where DFMA Goes Wrong (And How to Fix It)

Even with clear objectives, Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DFMA) programs can fail. These failures are rarely technical; they are organizational and procedural. Anticipating these common pitfalls is critical for engineering leaders to prevent costly mistakes that can jeopardize a product launch.

Pitfall 1: The Last-Minute “Manufacturability” Check

Problem: The design is considered “complete” and is then submitted for a manufacturability review just before tooling release. At this stage, the cost and schedule impact of any meaningful change is prohibitive. This turns DFMA into a reactive, adversarial process.

Solution: Mandate cross-functional design reviews from the earliest concept stage. Involve manufacturing, quality, and supply chain experts from day one and give them authority to influence the core architecture. This transforms DFMA from a late-stage gate into a continuous, collaborative process.

Pitfall 2: Lack of Quantitative Metrics

Problem: The DFMA initiative is guided by vague goals like “make it easier to build.” Without concrete targets, design choices are subjective, and the program’s ROI cannot be demonstrated.

Solution: Establish and track specific Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for every project.

- Part Count Reduction: Target a specific percentage reduction against a baseline.

- Assembly Time: Use a quantitative method like Boothroyd-Dewhurst analysis to estimate and set a target assembly time.

- First-Pass Yield (FPY): Define a target FPY that the design must enable at production launch (e.g., >98%).

A design is not complete until it meets both performance specs and manufacturability KPIs.

Pitfall 3: Designing Without Supplier Collaboration

Problem: The design team operates in isolation, without consulting the contract manufacturer (CM) or key suppliers. This ignores a critical source of process-specific expertise, resulting in a design that is difficult or expensive to produce on the supplier’s actual equipment.

Solution: Engage manufacturing partners under NDA as early as possible. Bring them into design reviews and ask for direct feedback: “How would you build this? What can we change to make it cheaper, faster, or more reliable on your production line?” This de-risks the production ramp by aligning the design with real-world manufacturing capabilities.

Pitfall 4: Optimizing Beyond the Point of Diminishing Returns

Problem: In the pursuit of cost reduction, teams can take principles too far. For example, consolidating too many functions into one hyper-complex part can make it unserviceable. Loosening tolerances to save manufacturing cost can compromise long-term product reliability. In regulated contexts (e.g., medical devices under ISO 13485), this can lead to catastrophic compliance failures.

Solution: Clearly define and document the non-negotiable requirements for performance, safety, and reliability before optimization begins. These serve as rigid guardrails. Use tools like Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to rigorously assess how cost-driven design changes might impact critical functions.

Accelerating Your Path to Manufacturing Excellence

Implementing a robust DFMA program requires integrated expertise across mechanical design, hardware engineering, firmware, and supply chain logistics. For companies facing aggressive timelines or complex technical challenges, assembling this cross-functional capability internally can be a significant hurdle.

An experienced engineering partner can provide this integrated expertise on demand. Sheridan Technologies operates a Dynamic Expert Network, allowing us to build elite teams precisely matched to your project’s challenges. From initial architecture to a supply-chain-ready final design, we bring hands-on experience from demanding industries like aerospace, robotics, and medical devices.

End-to-End Execution for First-Pass Success

We build for manufacturability and testability from day one. It’s in our DNA. This means we’re not just designing a PCB; we’re architecting it for high-yield production. We’re not just creating a mechanical enclosure; we’re using rapid prototyping and 3D printing to validate complex assembly steps long before you ever commit to expensive tooling.

This end-to-end approach closes the gap between design intent and manufacturing reality, ensuring first-pass success. We systematically de-risk your project at every stage, making sure the final product isn’t just functional, but is also efficient to build, test, and scale. You can see exactly how we structure these engagements in our process overview.

By embedding manufacturing and assembly logic into the earliest design phases, we prevent the costly rework and schedule delays that cripple product launches. Our goal is to make your design robust, reliable, and ready for production without compromise.

If you’re wondering how your current product development process stacks up, let’s talk. A confidential assessment with our engineering leads can quickly identify immediate opportunities to slash costs, mitigate risks, and get your product to market with confidence.

Frequently Asked Questions about DFMA

Practical questions often arise when implementing a Design for Manufacture and Assembly framework. Here are direct answers focused on operations and business impact.

When Should We Start Implementing DFMA?

Implementation must begin at the concept and architecture phase. The cost of a design change increases exponentially as a product moves from concept to production. Early decisions on materials, architecture, and manufacturing processes lock in the vast majority of a product’s final cost, quality, and supply chain risk.

Waiting until the detailed design is complete transforms DFMA from a proactive cost-avoidance strategy into a reactive and expensive rework project. By then, the most significant opportunities for optimization have been lost.

How Do We Measure the ROI of a DFMA Program?

The return on a DFMA program is measured through concrete Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that directly impact financial statements.

- Direct Cost Savings: Track the measurable reduction in Bill of Materials (BOM) cost from part count reduction, material optimization, and faster assembly times.

- Reduced Time-to-Market: A design optimized for manufacturing moves through prototyping and production ramp-up faster, accelerating time-to-revenue.

- Improved First-Pass Yield (FPY): A higher FPY on the manufacturing line directly reduces scrap and rework costs.

- Lower Warranty & Service Costs: Products designed for error-proof assembly and serviceability are more reliable, reducing warranty claims and field service expenses.

A comprehensive ROI analysis should also account for strategic benefits, such as increased production capacity and enhanced competitive positioning.

Is DFMA Relevant for Low-Volume or Complex Products?

Yes, the principles are universal, though the tactical focus may shift. For low-volume, high-complexity products in regulated industries like aerospace (DO-178C) or medical devices (ISO 13485), the priority may shift from pure cost reduction to ensuring absolute assembly correctness, reliability, and serviceability.

For instance, DFMA is used to design features that physically prevent the incorrect installation of a critical component, improve access for mandatory inspections, or ensure a process is repeatable to a six-sigma standard. In these contexts, DFMA is not just a cost-saving measure; it is a critical tool for ensuring safety, performance, and regulatory compliance. The goal remains the same: use design to mitigate risk and control the total lifecycle cost.

At Sheridan Technologies, we integrate DFMA principles from the initial concept through production-ready design, ensuring your product is not only innovative but also manufacturable, reliable, and profitable.

To de-risk your next project and accelerate your time-to-market, let’s discuss your objectives. Schedule a confidential assessment with our engineering leads.