Table of Contents

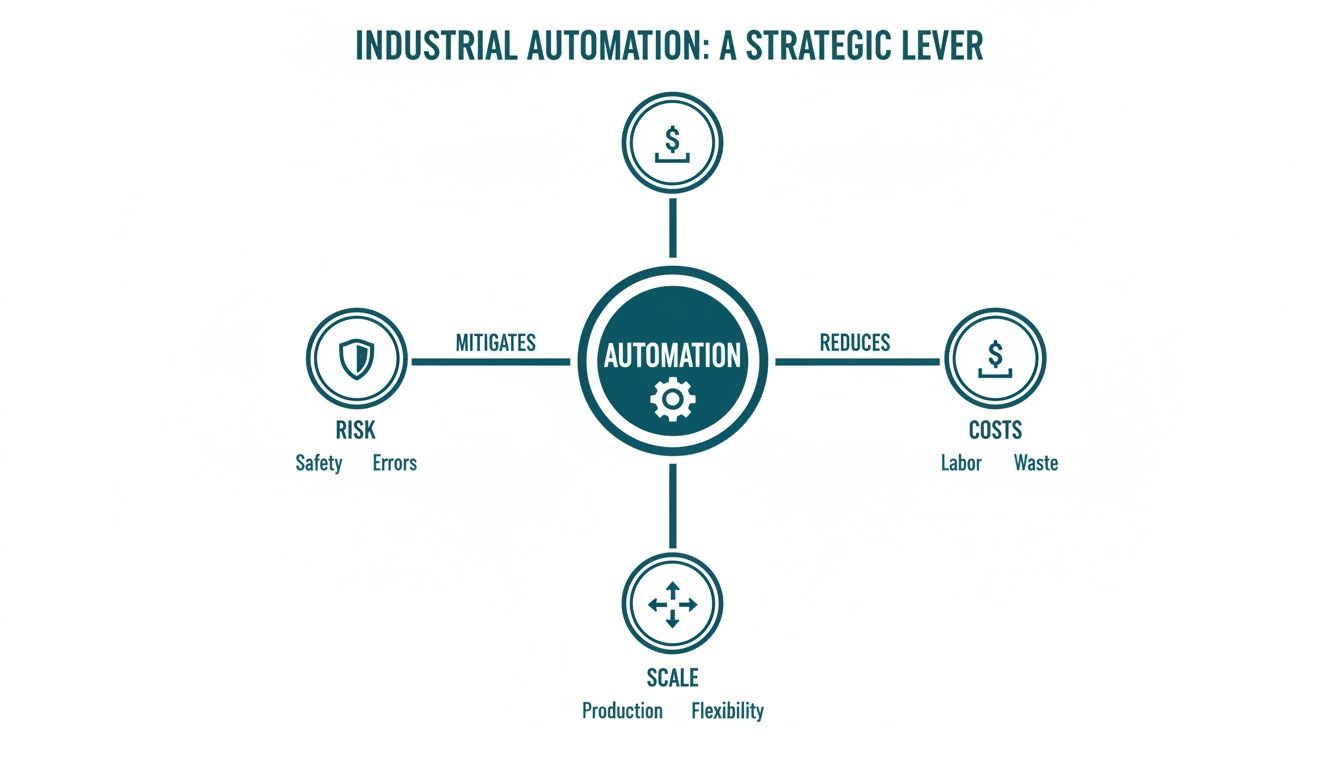

Industrial automation isn’t about deploying novel technology for its own sake. It’s the strategic application of control systems and robotics to run industrial processes with minimal human intervention, targeting significant gains in efficiency, reliability, and risk reduction. For operations leaders and C-suite decision-makers, it represents a powerful lever for controlling costs, mitigating operational risk, and building a business that can scale predictably.

Thinking of Industrial Automation as a Strategic Lever

Too often, automation projects become mired in technical minutiae. For time-constrained leaders, however, the only relevant discussion is how the technology solves a specific, costly business problem. Automation should be a strategic response to a business constraint, not a technology showcase.

This perspective forces every technical decision to answer a business question, transforming a capital expenditure into a competitive advantage. The focus shifts from features to measurable business impact—the only metric that matters in a high-stakes operational environment.

A Framework for Action: Problem → Diagnosis → Solution → Outcome

To maintain project focus and cut through technical jargon, frame every initiative using a clear problem-to-outcome sequence. This structure serves as a critical check to ensure you’re building a production asset, not a costly science experiment.

Real-World Scenario: Medical Device Manufacturing

Consider a mid-sized medical device manufacturer facing pressure from two fronts: inconsistent product quality is driving up scrap rates, while rising labor costs are eroding margins.

- Problem: Inconsistent quality and unsustainable labor costs are eroding profitability and hindering the ability to meet market demand.

- Diagnosis: A root cause analysis reveals that human variability in manual assembly and inspection is the primary driver. Even highly skilled operators introduce minute deviations, leading to a 5% scrap rate and unpredictable daily output. This variability also introduces significant compliance risk under frameworks like ISO 13485.

- Solution: The response is not simply “buy a robot,” but to engineer an integrated system. This includes a precision robotic arm for assembly, a machine vision system for 100% quality inspection, and a PLC to orchestrate the workflow with deterministic timing. The system doesn’t just assist the process; it is the process, ensuring repeatability.

- Outcome: The business impact is immediate and defensible. Scrap rates plummet from 5% to less than 0.5%. The production line achieves a predictable hourly output, enabling reliable forecasting. Skilled operators are reallocated to higher-value work, such as system maintenance, process optimization, and new product introduction.

This problem-first approach is non-negotiable. Without a precise diagnosis of the business challenge, an automation project is an unmanaged financial risk.

Moving Beyond Simple Cost Reduction

While labor cost reduction is a common justification, the deeper strategic value of industrial automation lies in risk mitigation and enabling scalable growth.

An automated system delivers a level of process consistency that is often unattainable with manual operations—a mandatory requirement for meeting stringent regulatory standards like ISO 13485 in medical devices or DO-178C in aerospace.

This consistency de-risks the entire production operation. It ensures that as demand scales, product quality and compliance remain stable. Understanding this strategic “why” is the critical first step, long before debating the “what” and “how” of the technology itself.

Understanding The Core Components Of Modern Automation Systems

For an operator or engineering lead, a successful automation project depends on a clear understanding of how system components interact. A useful analogy is to view an automation system as a biological entity: it has a brain (control logic), senses (sensors), muscles (actuators), and a nervous system (communication network) connecting it all.

This architectural perspective moves the conversation from a list of acronyms toward a clear system design. Foundational choices made at this stage determine the system’s reliability, scalability, and total cost of ownership.

The Brains and Nerves Of The Operation

At the core of any industrial automation solution are the control systems that execute logic and manage information flow with high precision.

- Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs): These are ruggedized, purpose-built computers that serve as the workhorses of the factory floor. A PLC’s sole function is to execute a specific control loop repeatedly and reliably, reading inputs from sensors and writing outputs to actuators. They are engineered for high-reliability, real-time performance in harsh industrial environments.

- Human-Machine Interfaces (HMIs): The HMI is the operator’s primary interface to the process. It’s typically a graphical touchscreen panel displaying system status, production data, and alarm conditions, allowing operators to monitor operations and issue commands.

- Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA): While a PLC controls a machine, a SCADA system provides a plant-level view. It aggregates data from multiple PLCs and other devices, offering a centralized command center for monitoring and controlling broader operations.

These components become strategic levers for the business—mitigating risk, containing costs, and enabling scale.

The key insight is that every component selection must serve a larger business objective. Technology choices must be directly traceable to strategic goals.

The Senses and Muscles

An automation system is inert without the ability to perceive and act upon its environment. This is the role of sensors and actuators.

- Sensors: These devices convert a physical property—such as temperature, pressure, position, or proximity—into an electrical signal that a PLC can interpret. They provide the essential feedback for precise, closed-loop control. For safety-critical applications, selecting certified components like a SIL2 compliant OEM gas analyser is necessary to ensure process integrity and personnel safety under standards like IEC 61508.

- Actuators: These components perform the reverse function, converting an electrical signal from the PLC into physical action. Examples include electric motors, hydraulic cylinders, pneumatic valves, and robotic arms. They are the “muscles” that execute the work.

Making the right trade-offs when selecting these components is a critical design discipline.

Comparing Core Automation Components And Key Trade-offs

This table provides a functional overview of key components, their primary role, and critical considerations during system design.

| Component | Primary Function | Key Selection Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) | Executes real-time control logic for a specific machine or process. | Reliability vs. Flexibility: Optimized for deterministic, hard real-time control but less suited for complex data processing or enterprise integration compared to IPCs. |

| HMI (Human-Machine Interface) | Provides a graphical interface for operator monitoring and control. | Cost vs. Functionality: Basic panels offer limited features, while advanced HMIs with scripting, data logging, and richer graphics carry a higher cost. |

| SCADA (Supervisory Control & Data Acquisition) | Gathers data from multiple PLCs for centralized, plant-wide monitoring and control. | Scale vs. Complexity: Essential for large-scale operations but introduces significant integration complexity and cost. |

| Sensors | Convert physical properties (temperature, pressure, etc.) into electrical signals. | Accuracy vs. Cost & Durability: Higher precision or ruggedization for harsh environments (e.g., IP67 rating) comes at a premium. |

| Actuators | Convert electrical signals into physical motion (motors, valves, etc.). | Power vs. Precision & Cost: Hydraulic/pneumatic systems offer high force density but less precision and higher operating costs than electric servos. |

Understanding these trade-offs is fundamental. The optimal component is always the one that best fits the specific technical requirements, budget, and long-term operational goals.

Evolving Architectures: The Rise Of IPCs And IIoT

The classic PLC-centric model is evolving. The demand for more data, advanced analytics, and machine learning is driving the adoption of more powerful and connected architectures.

An Industrial PC (IPC) is a ruggedized computer designed for the factory floor. While a PLC excels at deterministic control, an IPC provides superior processing power, memory, and networking capabilities. The transition to an IPC is justified when an application requires complex data logging, integration with ERP/MES systems, or execution of machine vision or AI algorithms at the edge. The trade-off is often a higher initial cost and the need for more specialized software development expertise.

The trend toward more powerful edge computing is a direct response to the data demands of Industry 4.0 and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). IIoT refers to the network of connected sensors, instruments, and devices collecting and sharing data. This data can be processed at the “edge” on an IPC for low-latency control decisions or sent to the cloud for large-scale analysis, predictive maintenance modeling, and long-term process optimization. The choice between edge and cloud computing is a trade-off between latency, data volume, security posture, and connectivity constraints.

Calculating the True ROI of Automation Investments

Justifying a major capital investment in industrial automation requires a credible financial model that goes beyond a simplistic labor cost calculation. While direct labor reduction is an obvious metric, it often represents the smallest portion of the total value.

A robust ROI analysis must quantify the second- and third-order effects of automation, connecting the investment to critical business drivers like risk mitigation, quality improvement, and increased throughput. The most compelling business case is often built by quantifying the high costs of the status quo—scrap, rework, warranty claims, and the financial and reputational threat of a product recall.

Building a Multifaceted ROI Model

A defensible financial model for an automation project should be built on several quantifiable pillars. This approach frames the investment as a strategic asset that delivers measurable returns across the entire operation.

- Improved Quality and Reduced Waste: Automation drives process consistency, which directly impacts material costs. Calculate your current cost of poor quality (CoPQ), including scrap and rework, as a percentage of revenue. Model a realistic reduction based on the proposed system’s capabilities; a 70-80% decrease in specific defect categories is often achievable.

- Increased Throughput and Capacity: An automated cell operates at a consistent, predictable rate, often 24/7. This increases overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) and allows for higher output without a proportional increase in fixed costs, directly improving gross margins.

- Enhanced Safety and Reduced Risk: Quantify the cost of workplace injuries by factoring in insurance premiums, lost work time, and potential regulatory fines. Automation can nearly eliminate incidents in high-risk manual tasks, representing a direct and defensible cost saving.

This disciplined approach to financial modeling shifts the conversation from “how much does it cost?” to “what is the cost of inaction?”

Real-World Scenario: Medical Device Manufacturing

A mid-sized manufacturer of sterile diagnostic kits faced an existential threat. Their manual assembly process was slow, highly susceptible to contamination, and created significant compliance risk under ISO 13485 standards.

- Problem: The risk of a product recall due to contamination posed an existential threat to the business, and production capacity was insufficient to meet growing market demand.

- Diagnosis: The financial model focused primarily on risk mitigation. The team calculated the probable cost of a single recall event at over $2 million, including product replacement, regulatory fines, and brand damage.

- Solution: An investment was made in a fully enclosed robotic assembly cell. The system handled, filled, and sealed the kits in a sterile environment, with integrated machine vision providing 100% quality inspection.

- Outcome: The ROI was justified almost entirely on risk avoidance. The automation eliminated the primary contamination vector, reducing the probability of a recall to near zero. As a secondary benefit, the system tripled production throughput, enabling the company to capture additional market share.

The most powerful ROI calculations are often rooted in risk reduction. For regulated industries, proving how an industrial automation solution mitigates a multi-million-dollar threat is a far more compelling argument than simple labor arbitrage.

Avoiding Common Financial Missteps

Even with a strong model, it is easy to miscalculate the total cost of ownership (TCO). Decision-makers must be realistic about hidden and recurring expenses that can undermine a project’s financial viability.

Be sure to account for:

- Integration and Commissioning Costs: These costs can often equal or exceed the hardware price. Factor in all hours for system integration, software development, factory acceptance testing (FAT), and site acceptance testing (SAT).

- Operator and Maintenance Retraining: Budget for comprehensive training programs to ensure the team can operate and maintain the new equipment safely and effectively.

- Ongoing Support and Spares: Plan for maintenance contracts, consumable parts, and a realistic budget for spare components to minimize mean time to repair (MTTR).

Overlooking these factors is a reliable way to exceed budget and erode the credibility of the initial ROI projection. A successful financial plan is both optimistic about the benefits and pragmatic about the total lifetime costs.

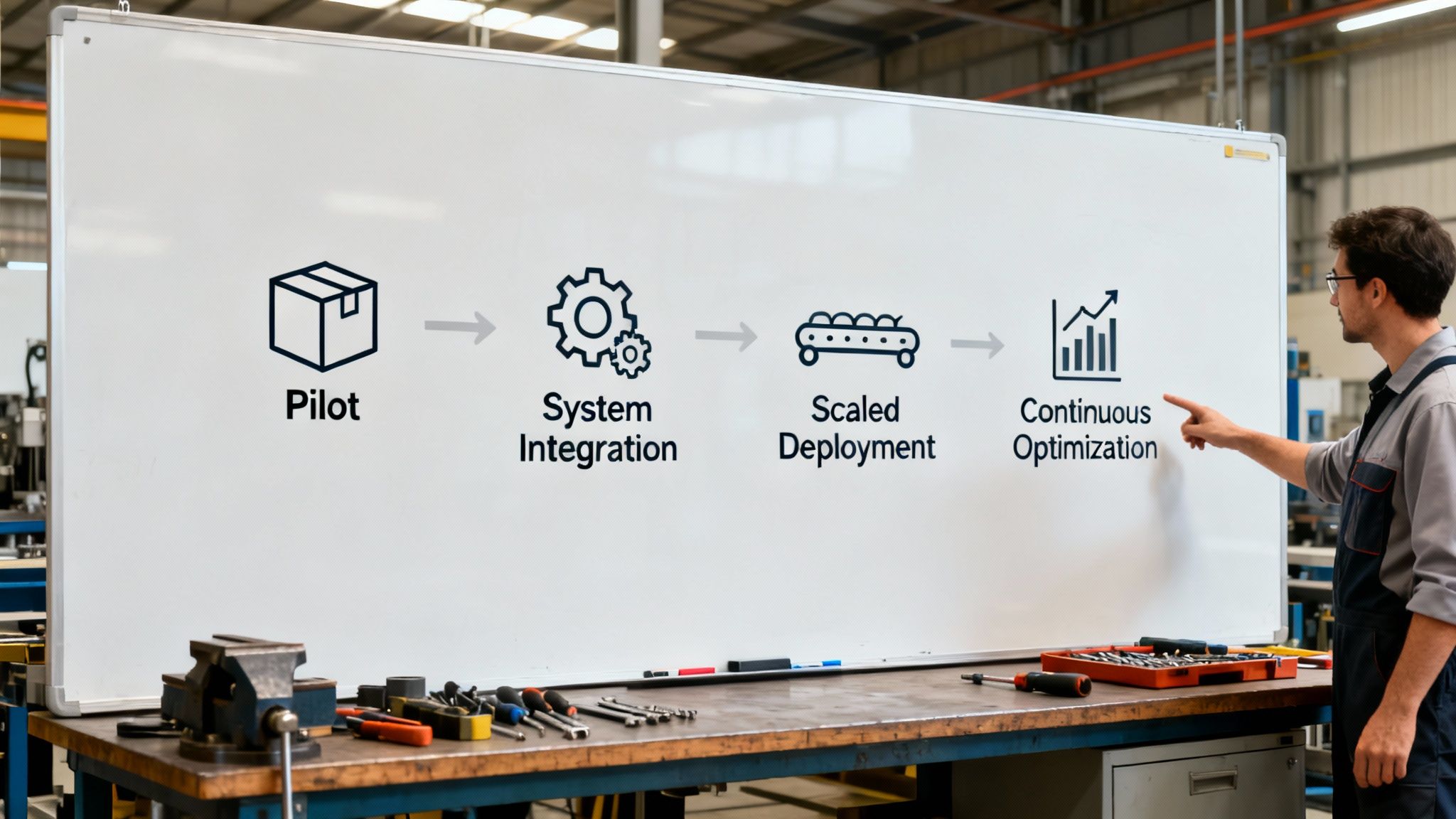

A Phased Roadmap for Implementing Automation Projects

Successful industrial automation is not implemented in a single step; it is a series of deliberate, managed phases. This phased approach is the only credible method to de-risk a complex technical initiative, validate assumptions, and avoid the costly stalls and budget overruns that plague poorly planned projects.

The process begins with a rigorous, data-driven analysis of the current state. What are your current cycle times, defect rates, and OEE metrics? Without these baseline numbers, you have no objective way to measure success or justify the investment.

Phase 1: The Pilot Project

The goal of a pilot is to prove the core concept on a small, manageable scale. The focus is not on full production volume but on targeted risk reduction. Your objective is to validate the most critical and uncertain elements of the proposed solution in a controlled environment.

This is where you confirm that the chosen robot, vision system, and control logic can perform the required task reliably. It is an opportunity to fail fast and inexpensively, uncovering technical issues before they can jeopardize the entire program. A successful pilot delivers the hard data and stakeholder confidence needed to secure investment for a full-scale deployment.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid:

- Over-Scoping: Resist the temptation to solve multiple problems at once. A pilot must have a single, sharply defined objective.

- Ignoring Production Realities: The pilot must use production-grade components and mimic real-world conditions, including material variations and environmental factors.

- Insufficient Data Collection: The primary output of the pilot is detailed performance data. This data is the foundation for all subsequent phases.

Phase 2: System Integration

With a validated concept, the project moves to integrating the pilot system into the broader production line. This phase requires the seamless convergence of mechanical, electrical, and software engineering. It involves physical installation, connection to upstream and downstream equipment, and communication with plant-level systems like SCADA.

This phase is notoriously complex and demands meticulous planning and coordination between internal teams and external integrators. Success hinges on robust testing, from the Factory Acceptance Test (FAT) at the integrator’s facility to the Site Acceptance Test (SAT) on your production floor. A thorough discovery phase of a project is the most effective way to identify and mitigate integration risks early.

Phase 3: Scaled Deployment

Once the first system is commissioned and stable, the next step is to scale. This involves replicating the successfully integrated system across other production lines or facilities. This is rarely a simple copy-paste operation; each deployment introduces new variables, from minor differences in plant layout to varying operator skill levels.

The key to managing this complexity is standardization. Every aspect of the solution—from the bill of materials (BOM) and control software to operator training documentation—must be meticulously documented and version-controlled. This discipline ensures consistency, simplifies maintenance, and reduces the long-term support burden.

A critical but often overlooked element of scaling is designing for manufacturability and testability from day one. Engaging experts early to validate concepts and ensure the design is robust, repeatable, and maintainable is the surest way to achieve first-pass success and avoid costly project stalls.

Phase 4: Continuous Optimization

The project does not end at go-live. The launch of a new automation solution marks the beginning of a continuous improvement cycle. The data generated by the automated process is a valuable asset for identifying further refinements.

This final phase leverages data from sensors and control systems to fine-tune performance. By analyzing production metrics, you can identify bottlenecks, reduce cycle times, and implement predictive maintenance strategies to maximize uptime. This iterative process ensures the system not only meets its initial ROI targets but continues to deliver increasing value over its operational life, turning a one-time project into a lasting competitive advantage.

Proven Use Cases Across Demanding Industries

The true measure of an industrial automation solution is its performance in real-world applications, particularly in industries where failure is not an option. Let’s examine how targeted automation solves specific operational challenges and delivers measurable returns.

Aerospace Composites Inspection

In aerospace, the structural integrity of every component is non-negotiable. Microscopic flaws in composite materials can propagate into catastrophic failures, making the inspection process both critical and a significant production bottleneck.

- Problem: A major aerospace supplier was constrained by the manual inspection of large composite fuselage panels. The process was slow, costly, and subject to human error—a major liability in their DO-178C regulated environment.

- Diagnosis: Manual inspection of a single panel by highly trained technicians required over 20 hours. Despite strict protocols, the risk of a missed subsurface flaw jeopardized safety and production schedules.

- Solution: A custom automated machine vision system was engineered. This integrated high-resolution imaging with intelligent algorithms to scan every square millimeter of the panels, detecting microscopic defects, delamination, and porosity far beyond the capabilities of human inspection.

- Outcome: The new system reduced inspection time by 90%, from over 20 hours to just two. More critically, it increased the probability of detecting critical flaws to 99.9%, providing irrefutable quality data for compliance with aviation safety standards.

AgriTech Precision Irrigation

For large-scale agricultural operations, water is a primary input cost and a critical resource. Traditional, schedule-based irrigation methods are often inefficient, wasting water while failing to meet the specific needs of the crops.

- Problem: A large commercial farm was experiencing rising water costs and inconsistent crop yields. Their fixed-schedule sprinkler system was a blunt instrument, over-watering some areas while under-watering others.

- Diagnosis: Soil moisture levels varied significantly across hundreds of acres due to differences in soil type, sun exposure, and topography. A one-size-fits-all watering schedule was inherently inefficient, wasting both water and money.

- Solution: An IIoT-driven system was deployed, centered around a network of wireless soil moisture sensors. This provided real-time data from across the fields to a central control platform, which used predictive analytics to deliver the precise amount of water each zone required.

- Outcome: In the first growing season, the farm reduced water consumption by 30%. Concurrently, by eliminating crop stress from over- and under-watering, crop yields increased by 15%.

This is a classic example of data-driven automation converting a major cost center into a source of efficiency and profit. The ROI is realized not only in reduced input costs but also in increased revenue from higher yields.

Medical Device Assembly

In medical device manufacturing, consistency is a regulatory mandate. For a new diagnostic cartridge, the slightest assembly variation could compromise test accuracy, jeopardizing patient safety and regulatory approval.

- Problem: A medical diagnostics company faced surging demand for a new testing cartridge that outstripped the capacity of its manual assembly process. The process was too slow and could not deliver the precision required for ISO 13485 compliance.

- Solution: A compact, robotic assembly cell was designed and integrated into their cleanroom environment. The system combined precision robotics and integrated vision guidance to handle, fill, and seal the delicate cartridges with perfect, repeatable accuracy on a 24/7 basis.

- Outcome: The automated cell enabled a 400% increase in production volume while maintaining a near-zero defect rate. This solved the immediate production bottleneck and provided a scalable platform for future growth, all while ensuring every step was auditable and compliant with medical device regulations.

These examples demonstrate how well-executed automation targets specific business problems with appropriate technology to achieve measurable results. You can see more industrial automation case studies that follow this same practical, problem-solving approach.

Navigating Project Rescue and Future-Proofing Your Systems

Not every industrial automation project succeeds as planned. Promising initiatives can stall, plagued by technical issues that result in underperforming equipment and budget overruns. These failures are typically not a single event but a gradual accumulation of missed deadlines, persistent bugs, and a system that fails to achieve stable operation.

When a project derails, the first step is technical triage. The common reaction is to blame hardware or the integrator, but the root cause is often more subtle. A disciplined diagnostic process is required to identify the true source of the problem, whether it lies in embedded control firmware, a hardware integration mismatch, or a fundamental flaw in the mechanical design.

A Real-World Project Rescue

Consider a packaging line upgrade sold on the promise of a 40% throughput increase. After installation, the system is unstable, faulting constantly and achieving only a fraction of its target speed.

- Problem: The machine is mechanically sound but suffers from random, unpredictable stops that cripple production. The original integrator is unable to resolve the issue.

- Diagnosis: An external specialist is engaged. Instead of only analyzing PLC logic, they investigate the embedded firmware controlling the servo motors. They discover a race condition—a timing bug—that only manifests at high operational speeds, causing the controllers to fault randomly. To unravel this type of issue, a structured approach is critical. Our guide on root cause analysis for engineering provides a framework for these complex investigations.

- Solution: A firmware specialist patches the code, recompiles it, and validates it through a rigorous testing process to eliminate the timing conflict.

- Outcome: With the firmware corrected, the system immediately achieves and sustains its target speed. The project is recovered, meeting and exceeding the original 40% throughput goal and salvaging the entire capital investment.

This scenario highlights a critical point: a stalled project is often one specialist away from a breakthrough. Identifying the true root cause is paramount.

Building Systems That Last: Strategies for Future-Proofing

“Future-proofing” is not about selecting the newest components; it is a strategic approach to design and management that builds long-term resilience.

- Embrace a Modular Design: Architect systems with well-defined, interchangeable modules. This allows for the upgrade of a single component—such as a vision system or a robot’s end-of-arm-tooling—without re-engineering the entire line.

- Insist on Open Standards: Whenever possible, avoid proprietary, closed ecosystems. Using open communication protocols (e.g., OPC-UA) and standard hardware interfaces prevents vendor lock-in and simplifies future upgrades and support.

- Plan for Obsolescence: Every hardware component has a finite lifecycle. Maintain a detailed bill of materials and actively track end-of-life notices from suppliers to prevent a future crisis when a critical part becomes unavailable.

A core element of future-proofing is shifting from reactive to proactive maintenance. Implementing data-driven predictive and preventive maintenance strategies can significantly improve uptime and operational efficiency.

Choosing the Right Partner for Automation Success

Integrating an industrial automation solution is a high-stakes endeavor. Success requires more than just good hardware; it demands a seamless fusion of software, firmware, mechanical design, and system-level engineering. The path from concept to a reliable, scaled deployment is fraught with risks, from miscalculated ROI to integration failures that can halt an entire operation.

This is why selecting the right partner is less about finding a vendor and more about securing a dedicated engineering ally. You need a team that operates as an extension of your own, providing the specialized, multidisciplinary expertise needed to navigate complex trade-offs and ensure successful execution. This is especially critical when rescuing a stalled project or pushing the boundaries of what is technically feasible.

The Value of On-Demand Expertise

An effective partner provides access to a deep bench of specialists—firmware engineers, hardware designers, mechanical experts—who can be deployed at the precise moment their skills are needed. This model avoids the massive overhead of maintaining a large, specialized internal team while ensuring elite talent is focused on the specific challenge at hand.

The single greatest value an end-to-end partner provides is de-risking the entire process. By focusing on design for manufacturability (DFM) from the outset and possessing the capability to triage a failing project, they convert complex automation challenges into predictable, successful outcomes. This strategic engagement transforms a capital expense into a durable competitive advantage by ensuring the system delivers its promised business impact.

At Sheridan Technologies, we specialize in solving complex engineering challenges in industrial automation. Whether you are commissioning a new system or need to recover a stalled project, our team has the expertise to deliver.

Schedule a brief, confidential technical assessment with a senior engineer to map out a clear path forward.