Table of Contents

Building a successful IoT app is a systems engineering challenge, not just a software project. A staggering 90% of your project’s success is determined before a single line of firmware is written. Nailing down the operational context, business goals, and non-negotiable performance metrics upfront is the primary mechanism to sidestep a costly, field-deployed failure.

Defining the Strategic Foundation for Your IoT Application

The initial requirements definition phase is the most critical stage of any serious IoT project. Teams that rush this stage consistently face budget overruns, missed deadlines, and products that fail under real-world conditions. Before architecting a solution, you need a precise requirements document that translates business objectives into concrete, measurable engineering targets.

This document serves as your primary risk mitigation tool. It forces alignment across hardware, firmware, and software teams, ensuring all efforts are directed toward the same well-defined goal. For decision-makers, this requires moving beyond a simple feature list to map the entire operational envelope of the device—from user workflows and environmental conditions to complex regulatory constraints.

From Business Need to Technical Specification

The core task is converting a business problem into a set of technical parameters that engineers can execute against. A vague request like “we need real-time monitoring” is unactionable and invites scope creep.

Engineering requires precision. That “real-time” requirement should be translated into a specific performance target: “The device must transmit a 256-byte payload every 500 milliseconds with a maximum end-to-end latency of 100ms and maintain 99.99% uptime.”

This level of detail eliminates ambiguity and establishes clear pass/fail criteria for validation. Key areas that must be rigorously defined include:

- Performance Metrics: Define exact figures for data throughput, system latency, and required availability.

- Power Budget: Specify the maximum power consumption in all operational states (e.g., active, sleep, transmit). This directly informs hardware selection and battery life models.

- Environmental Resilience: Quantify the operational limits, including temperature ranges, humidity tolerance, and the required IP rating for dust and water ingress.

- Regulatory Frameworks: Identify all applicable standards from day one. For a medical device, software lifecycle processes must be designed for compliance with IEC 62304. For an industrial controller, this may involve specifying Safety Integrity Levels (SIL) based on IEC 61508.

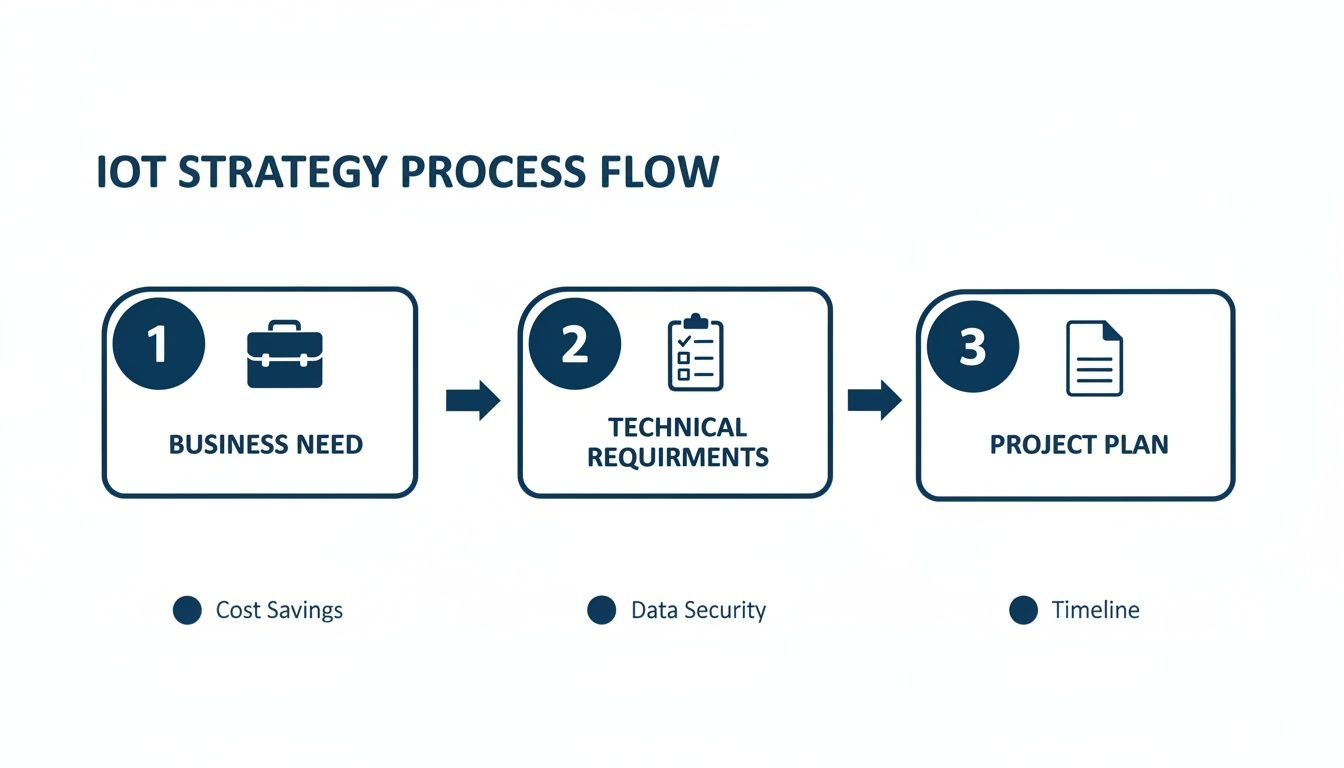

This discovery process is a logical flow, moving from the core business driver to the hard technical requirements that form the bedrock of a solid project plan.

As the diagram shows, a reliable project plan can only be built on a foundation of rigorously defined technical requirements that directly solve the business problem. There are no shortcuts.

To help structure this process, here is a checklist of the critical domains your team needs to address during this initial planning and requirements definition phase.

Key Requirements Definition Checklist for IoT Projects

This table outlines the essential areas to cover. Skipping any one of these can introduce significant risk later in the project.

| Domain | Key Considerations | Example Metric or Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Business & User | What is the core problem being solved? Who is the user? What is the business model? | Reduce equipment downtime by 15% within 12 months. |

| Performance | Data throughput, latency, update frequency, system response time. | <200ms end-to-end latency from sensor to cloud. |

| Connectivity | Wi-Fi, Cellular (LTE-M, NB-IoT), LoRaWAN, Bluetooth? Data plan costs? | Must maintain connectivity in areas with -120 dBm cellular signal. |

| Hardware & Power | CPU/memory constraints, sensor accuracy, battery life, power states. | 5-year battery life with one transmission per hour. |

| Environment | Operating temperature, humidity, vibration, ingress protection (IP rating). | Operate between -20°C to 85°C; IP67 rated enclosure. |

| Security | Data encryption (at rest/transit), authentication, secure boot, OTA update security. | Implement TLS 1.3 for all communications; use encrypted flash storage. |

| Compliance | FCC/CE, UL, RoHS, industry-specific standards (e.g., IEC 62304 for medical). | Achieve FCC Part 15 certification prior to mass production. |

| Manufacturing | Design for Manufacturability (DFM), component sourcing, test procedures. | All components must have at least two qualified suppliers. |

Working through a checklist like this ensures all bases are covered and forces the difficult but necessary conversations to happen early.

Diagnosing Failure Before It Happens

The stakes in the IoT market are high. According to IoT Analytics, the number of connected IoT devices reached 16.7 billion globally in 2023, with continued growth expected. This expansion, driven by industrial, consumer, and enterprise sectors, makes robust IoT app development a critical business capability.

With significant capital and opportunity on the line, a disciplined discovery phase is non-negotiable. It’s a structured process that forces your team to confront potential points of failure when they are still just ideas on a whiteboard—not expensive problems in the field.

By rigorously defining the ‘what’ and ‘why’ before getting lost in the ‘how,’ you transform IoT development from a high-risk gamble into a predictable engineering discipline. The goal is to make the build phase an exercise in execution, not exploration.

Getting this wrong leads to predictable outcomes: selecting an inadequate microcontroller, writing firmware that cannot meet performance targets, or building an application that fails to solve the user’s problem. A well-run discovery phase, like the one we detail in our guide on the discovery phase of a project, is the single best investment you can make to de-risk your project and ensure a successful outcome.

Architecting for Reality: Hardware, Firmware, and Connectivity

A successful IoT product is a systems engineering challenge where digital and physical constraints collide. Projects often fail at the seams where hardware, firmware, and connectivity intersect.

Treating these as separate silos introduces significant risk of budget overruns, schedule delays, and a product that fails under real-world stress. The only viable path is to architect these three pillars as a single, interdependent system from day one.

Every choice has downstream consequences. For example, selecting a low-power, resource-constrained microcontroller to meet a five-year battery life goal immediately impacts the firmware team. It limits available processing power, potentially precluding sophisticated edge AI workloads. This may force more computation to the cloud, which in turn increases latency and data transmission costs. This is not just a technical trade-off; it’s a business decision that affects unit cost, user experience, and operational scalability.

Making Critical Connectivity Choices

Selecting a connectivity protocol requires a rigorous analysis of the device’s operational environment. The decision must balance data throughput, range, power consumption, and long-term cost. A solution ideal for a smart factory floor is often completely unsuitable for a sensor deployed in a remote agricultural setting.

The key is to map the requirements defined in the strategy phase directly to the real-world performance of each protocol.

- LoRaWAN: Suited for static, low-power devices transmitting small, infrequent data packets over long distances (kilometers). Its low data rate makes it impractical for firmware updates or streaming rich data.

- NB-IoT/LTE-M: A strong choice for applications requiring broad coverage via existing cellular networks. They offer a good balance of power efficiency and higher data rates than LoRaWAN, making them suitable for mobile or more dynamic use cases.

- Wi-Fi (specifically Wi-Fi 6/HaLow): Best for high-throughput applications in localized areas with available mains power. It is generally a poor fit for battery-powered devices spread across a wide geographic area.

- 5G: Offers extremely high speed and ultra-low latency but comes at a significant cost and power consumption penalty. It is typically reserved for demanding applications like autonomous vehicles or real-time industrial robotics.

To put these choices into perspective, it’s helpful to see their key characteristics side-by-side.

IoT Connectivity Protocol Trade-Offs

Choosing the right connectivity protocol is a critical decision point in IoT architecture. The following table provides a comparative analysis of common options, highlighting the trade-offs between range, data rate, power consumption, and ideal application scenarios. This isn’t an exhaustive list, but it covers the major players you’ll be evaluating.

| Protocol | Typical Range | Data Rate | Power Consumption | Best-Fit Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wi-Fi | ~50-100 meters | Very High (Mbps-Gbps) | High | Smart home devices, office automation, local video streaming |

| Bluetooth/BLE | ~10-100 meters | Low to Medium (Kbps-Mbps) | Very Low | Wearables, personal health monitors, asset tracking beacons |

| LoRaWAN | 2-15+ kilometers | Very Low (0.3-50 Kbps) | Extremely Low | Smart agriculture, remote metering, environmental monitoring |

| NB-IoT / LTE-M | 1-10+ kilometers | Low to Medium (Kbps-Mbps) | Low | Smart city applications, asset trackers, logistics monitoring |

| 5G | Varies (Meters to Km) | Extremely High (Gbps) | Very High | Autonomous vehicles, AR/VR, real-time industrial control |

As you can see, there is no single “best” protocol. The optimal choice is always dictated by the specific requirements of the product—the environment it will live in, the data it needs to send, and the battery life it must achieve.

The number of connected devices continues to grow rapidly. You can read more about the number of connected IoT devices and market trends to get a sense of the scale. This expansion creates intense demand for efficient IoT development, particularly in high-stakes industries like aerospace, defense, and medical devices, where flawless hardware and firmware integration is a baseline requirement.

A Real-World Scenario: Hardware Choices and Downstream Pain

Consider a team developing a GPS asset tracker for shipping containers.

Problem: To reduce the bill of materials, the team selects a low-cost GPS module with an integrated cellular modem. The datasheet specifications appear suitable, and it features aggressive power-saving modes. The hardware lead is recognized for reducing the per-unit cost.

Diagnosis: During integration testing, significant problems emerge. The firmware team discovers the module’s deep sleep mode is difficult to manage. Waking the module to re-establish a network connection requires a complex, poorly documented command sequence. The process takes an unpredictable amount of time—sometimes up to two minutes—causing the device to miss its scheduled data transmission window. The critical failure mode: the module sometimes fails to wake entirely, requiring a hard power cycle. This is a catastrophic failure for a sealed, battery-powered device intended to operate autonomously for years.

This is a classic example of a hardware decision made in a silo. The laser focus on component cost completely ignored the second-order effects on firmware complexity, reliability, and ultimately, the entire business case.

Solution: The team is forced into a costly and time-consuming redesign. They replace the problematic module with a slightly more expensive component from a reputable supplier known for robust firmware and comprehensive documentation. The new module features a clean, well-defined API for managing power states, which dramatically reduces firmware complexity.

Outcome: While the unit cost increased by $3, the project was substantially de-risked. The team recovered weeks of schedule that would have been lost debugging the original firmware. The final product achieved much higher reliability, significantly reducing the business risk of field failures and warranty claims. This scenario highlights a core principle of IoT development: optimizing for the lowest component cost often leads to a much higher total cost of ownership. A holistic architectural approach that validates hardware and firmware interactions early is essential to avoid these predictable failures.

Navigating Cloud and Edge Compute Architectures

Deciding where IoT data is processed is a critical architectural decision that directly impacts cost, latency, reliability, and scalability. An improper balance can result in a system that is too slow, too expensive to operate, or non-functional during network outages.

This is not a simple “cloud vs. edge” dichotomy. It is about designing a distributed system where computation occurs in the most appropriate location. The guiding question should be, “What is the business consequence of latency for this specific action?” This grounds the architecture in operational reality.

When Edge Computing is Non-Negotiable

For some applications, the latency of a round-trip to the cloud introduces an unacceptable level of risk. These are situations where immediate, deterministic action is required, independent of network status.

Consider these hard real-time or mission-critical scenarios:

- Industrial Robotics: A robotic arm on a factory floor cannot wait for cloud confirmation to avoid an obstacle. Motor control loops require sub-millisecond responses that are physically impossible to achieve over a wide area network.

- Medical Devices: An infusion pump must deliver medication accurately, even if the hospital’s Wi-Fi network is congested or unavailable. Critical logic for dose calculations and safety alerts must reside on the device, a requirement often mandated by standards like IEC 62304.

- Autonomous Systems: A drone navigating in a confined space relies on local sensor fusion to make instantaneous flight adjustments. Here, latency is a direct safety hazard.

In these cases, edge computing is a fundamental requirement for system function. While processing data at the source can reduce bandwidth costs, its primary benefit is often guaranteeing operational continuity.

The Case for a Cloud-Centric Model

Conversely, a system that operates exclusively at the edge can become a data silo, unable to leverage fleet-wide insights. The cloud is unparalleled for tasks requiring massive computational power, long-term data storage, and a consolidated view of an entire device fleet.

Cloud-first architectures are appropriate for:

- Big Data Analytics: Aggregating telemetry from thousands of devices to identify performance trends or implement predictive maintenance algorithms.

- AI Model Training: Using large historical datasets to train complex machine learning models is computationally infeasible on resource-constrained edge devices.

- Fleet Management: A central platform is essential for monitoring device health, deploying Over-the-Air (OTA) updates, and managing security credentials across the network.

A smart agriculture system illustrates this balance. Edge devices might control local irrigation valves based on real-time soil moisture readings, but all sensor data is streamed to the cloud. There, it is aggregated and analyzed to generate optimized watering schedules that are then pushed back down to the devices.

The optimal architecture for most sophisticated IoT systems is not purely edge or purely cloud. It is a hybrid model that intelligently partitions workloads. The goal is to handle time-sensitive, critical tasks at the edge while leveraging the cloud for heavy computation and long-term analysis.

Implementing a Hybrid Architecture

A hybrid model provides the benefits of both approaches but introduces challenges, primarily around managing distributed logic and ensuring data consistency.

Let’s walk through a real-world scenario.

Problem: A logistics company deploys asset trackers on its shipping containers. These trackers must operate reliably in remote areas with intermittent cellular coverage (an edge requirement). Simultaneously, dispatchers need a centralized dashboard providing the real-time status of the entire fleet (a cloud requirement).

Diagnosis: A tracker reliant solely on the cloud would become non-operational upon losing its connection, creating significant operational blind spots. A purely edge device would collect data but could not provide the live visibility required by dispatch.

Solution: The team implements a hybrid architecture. The device firmware manages all critical GPS tracking and sensor logging locally, storing the data in a queue on the device. When a network connection is available, an agent on the device transmits the queued data to the cloud backend.

Outcome: This store-and-forward pattern ensures 100% data integrity, even with unreliable connectivity. The cloud platform provides the high-level fleet view for dispatchers, while the edge device guarantees autonomous operation in the field. This design directly reduces the business risk of lost data and enhances operational reliability without requiring a constant—and expensive—cellular connection. This thoughtful blend of edge autonomy and cloud intelligence is the hallmark of mature iot apps development.

Weaving in Robust Security and Compliance from the Start

In professional IoT applications, security is not a feature; it is the foundation of the system. Attempting to add security as an afterthought is a common and critical failure. An unsecured device can become a significant liability—a vector for data breaches, a node in a DDoS botnet, or a direct physical safety hazard.

Adopting a “security-by-design” philosophy is the only credible approach. This means architecting security into every layer, starting at the silicon level. This involves using hardware security modules (HSMs) and secure boot processes to create a hardware root of trust, guaranteeing that the device only executes cryptographically signed, trusted firmware.

This foundational step is non-negotiable. For a deeper analysis, see our guide to security in embedded systems.

From this trusted hardware base, security measures must extend throughout the system—to every communication packet, data store, and API call.

Mitigating the Most Critical IoT Threats

Threat modeling—the process of identifying and prioritizing potential threats—is a crucial early step. In our experience, several common attack vectors appear in nearly every IoT project.

Here’s how we mitigate them:

- Device Spoofing: An attacker impersonates a legitimate device to inject malicious data. The primary defense is strong, unique device identity. This is typically achieved using X.509 certificates provisioned during manufacturing, which enable mutual TLS (mTLS) authentication with the cloud backend.

- Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks: An attacker intercepts and potentially alters communication between the device and the cloud. The only effective countermeasure is end-to-end encryption. Use modern, robust protocols like TLS 1.3 for TCP-based communication or DTLS for UDP.

- Firmware Tampering: Secure boot is the key mitigation. By using cryptographic signatures to verify firmware integrity at each boot cycle, you ensure that no unauthorized code can be executed.

- Data-at-Rest Breaches: If an attacker gains physical access to a device, they could potentially extract sensitive data from its non-volatile memory. Encrypting the flash storage makes the data unreadable even if the memory chip is physically removed from the board.

Integrating these practices into the development workflow is essential. The Secure Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) provides a structured framework for incorporating security at every stage.

Aligning with Compliance Frameworks

In regulated industries such as medical devices or industrial controls, compliance with specific standards is a prerequisite for market access.

Proactively aligning the system design with established cybersecurity frameworks is a strategic necessity.

A valuable example is the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, particularly the NISTIR 8259 series, which is tailored for IoT devices. It provides a practical checklist for core security capabilities, including:

- Device Identification: Every device must have a unique, unchangeable identifier.

- Data Protection: Concrete measures are required to secure data both at rest on the device and in transit.

- Secure Updates: A reliable and secure mechanism for delivering and applying firmware updates is mandatory.

By mapping your architecture to these guidelines from the outset, you not only reduce risk but also streamline the formal certification process later on.

A truly secure IoT system is designed for resilience, operating under the assumption that attacks will occur. It incorporates capabilities to detect threats, respond appropriately, and recover securely. This proactive, resilient posture is what separates professional-grade products from expensive failures.

The need for this discipline is growing. According to IoT Analytics, enterprise IoT spending is projected to grow from $237 billion in 2023 to $483 billion in 2028. As major sectors deploy millions of devices, the potential attack surface is expanding at an alarming rate, making a security-first approach a core business imperative.

Mastering the Lifecycle: Validation, Deployment, and Management

Achieving product launch is a milestone, but the long-term success of an iot apps development project is determined by its performance over years in the field, not its behavior on a test bench. The post-development lifecycle—encompassing validation, deployment, and ongoing management—is where product value is ultimately realized or lost.

The first critical gate is robust validation that extends beyond simple unit tests. It requires comprehensive strategies that test the device against the harsh, unpredictable conditions of its target environment. This represents a critical shift from a prototype mindset to a production-ready discipline, a journey detailed in our guide on moving from prototype to product.

Forging Resiliency Through Rigorous Testing

To ensure a product is field-ready, the validation process must be unforgiving. It must stress the entire system—from silicon to the cloud—under conditions designed to identify failure modes.

Key validation methodologies include:

- Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Simulation: This technique allows for testing firmware against a simulated model of the physical world. For an industrial controller, one can simulate motor feedback and sensor inputs to verify control logic without risking expensive physical machinery.

- Environmental Stress Testing: Devices must be validated against their specified environmental limits. This often involves placing units in a thermal chamber and cycling them between maximum and minimum operating temperatures to identify latent solder joint failures, component tolerance issues, or enclosure weaknesses before they manifest in the field.

- End-to-End Integration Testing: This validates the entire data pipeline, confirming that a sensor reading propagates correctly from the device, through the connectivity protocol, to the cloud platform, and is accurately represented in the end-user application.

Designing a Bulletproof OTA Update Mechanism

An Over-the-Air (OTA) update capability is non-negotiable for any modern IoT device. However, a poorly designed OTA system introduces one of the single greatest risks to a deployed fleet. A failure can render devices permanently inoperable, or “bricked.”

Common OTA failure modes include:

- Bricked Devices: An update fails mid-installation without a reliable rollback mechanism, leaving the device unresponsive.

- Update Storms: A naive implementation where thousands of devices request a large update file simultaneously can overwhelm servers and incur significant data costs.

- Security Vulnerabilities: An unsecured OTA process creates a vector for attackers to inject malicious firmware.

The core principle of a reliable OTA system is atomicity. An update must either complete 100% successfully, or the device must automatically roll back to its last known good state. There is no middle ground.

This is best achieved using a dual-partition scheme in the device’s flash memory. The new firmware is downloaded to an inactive partition. Only after the download is complete and its cryptographic signature is verified does the bootloader switch to the new partition. If the new firmware fails to boot, the system automatically reverts to the previous, functional partition.

To ensure your IoT application’s development, validation, and management are robust and efficient, consider adopting essential SDLC best practices.

Fleet Management and Diagnostics at Scale

Once devices are deployed, the challenge shifts to efficient management and monitoring. A robust device management platform provides centralized command and control. The objective is to gain deep visibility into the health and performance of every device, enabling a shift from reactive to proactive support.

A mature fleet management strategy enables you to:

- Monitor Key Metrics: Track device connectivity status, battery levels, memory usage, and application-specific health indicators in real-time.

- Perform Remote Diagnostics: Securely access device logs and execute diagnostic commands to troubleshoot issues without the high cost of dispatching a field technician.

- Manage Device Groups: Organize devices by customer, location, or firmware version to enable controlled, phased rollouts of updates and configuration changes, mitigating the risk of a “big bang” release.

Mastering the product lifecycle is ultimately about controlling the total cost of ownership (TCO). A system designed for robust validation, resilient updates, and efficient management minimizes costly field failures and support overhead, ensuring the long-term viability of your IoT investment.

Frequently Asked Questions About IoT App Development

During an IoT project, critical questions with significant business implications are inevitable. Here are some of the most common challenges that decision-makers and technical leads face.

What Are the Most Common Failure Points in an IoT Development Project?

IoT projects typically fail not from a single catastrophic event, but from an accumulation of unaddressed complexities at the intersection of hardware, firmware, and the cloud backend. Teams consistently underestimate the difficulty of ensuring these disparate domains operate reliably in uncontrolled field environments.

Common failure modes include:

- Hardware and Firmware Mismatch: A hardware component is selected based on cost, but it lacks the performance to meet firmware requirements. For example, a low-power MCU may be unable to handle core application logic concurrently with a secure TLS handshake, resulting in unacceptable performance.

- Unreliable Connectivity: A protocol that performs well in a lab environment often fails in the field. Selecting LoRaWAN for an application requiring frequent, large data transfers is a classic example of a mismatched tool.

- A Disastrous OTA Update Strategy: A simplistic Over-the-Air (OTA) update mechanism without a robust rollback feature is a significant liability. A single failed update due to a transient network issue can permanently brick thousands of devices, necessitating a costly physical recall.

- A Backend That Can’t Scale: An architecture designed for a few dozen test devices will often fail under the load of thousands of production devices connecting simultaneously. This leads to data loss, high latency, and system-wide outages.

The primary defense is a holistic, systems-thinking approach from day one, where every technical decision is evaluated for its impact across the entire system.

How Do You Choose Between Building vs. Buying Key IoT Platform Components?

This strategic decision balances the need for total control and customization against the need for speed to market and reduced operational overhead. The choice to build or buy components like a device management platform or a data ingestion pipeline requires careful consideration.

The decision framework should be based on an honest assessment of what is core to your competitive differentiation versus what is a commodity utility.

Build what gives you a competitive edge or solves a problem unique to your business; buy everything else that’s a commodity. An ag-tech company should pour its resources into building the secret sauce for crop yield analytics, not reinventing the wheel by building a generic MQTT broker from scratch.

The trade-offs are:

- Building: This provides maximum control to tailor a solution to exact requirements. However, it represents a significant, ongoing engineering investment and saddles your organization with long-term maintenance responsibility. You must be certain your team possesses the deep expertise in areas like distributed systems and cybersecurity.

- Buying/Licensing: Platforms like AWS IoT Core or Azure IoT Hub can significantly accelerate development timelines. The trade-offs include potential vendor lock-in and reduced architectural flexibility, as your system must operate within the constraints of the provider’s features and pricing models.

Often, a hybrid approach is optimal: buy foundational commodity services and build the unique application and analytics layers that deliver direct value to customers.

What Is the Role of a Digital Twin in Modern IoT App Development?

A digital twin is more than a 3D model; it is a high-fidelity, virtual representation of a physical IoT device, continuously updated with real-time data from its physical counterpart. Its primary purpose is to de-risk, accelerate, and optimize the entire product lifecycle.

During development, a digital twin allows firmware engineers to simulate complex scenarios without physical hardware. For instance, you can test how a motor controller’s firmware responds to a simulated mechanical failure—a test that would be destructive and expensive to conduct on real equipment. This accelerates validation and reduces dependencies on hardware availability.

After deployment, the digital twin becomes an essential operational tool.

- Real-World Scenario: Consider a fleet of industrial pumps. Each physical pump streams vibration, temperature, and pressure data to its corresponding digital twin in the cloud. An analytics model running against these virtual twins can identify subtle anomalies indicative of an impending failure. Instead of reacting to a costly outage, the system can automatically schedule predictive maintenance, dispatching a technician with the correct parts before the pump breaks down.

This is how raw IoT data is transformed into actionable intelligence that directly reduces operational downtime and maintenance costs.

How Should We Approach Prototyping vs. Production Design?

These are distinct phases with different objectives. Confusing them is a common and costly error.

Prototyping is focused on learning and risk reduction. Its sole purpose is to validate core assumptions as quickly and inexpensively as possible. This phase prioritizes speed, utilizing off-the-shelf development boards (from companies like Toradex or Digi), 3D-printed enclosures, and pre-certified modules. The deliverable is not a product; it is validated knowledge.

Production Design, in contrast, is focused on reliability, cost optimization, and Design for Manufacturability (DFM). This phase involves formal engineering discipline, with a focus on:

- Designing custom Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs) to meet specific form factor and performance requirements.

- Selecting components with stable, long-term supply chains and negotiating volume pricing.

- Ensuring the design can pass all necessary regulatory certifications, such as FCC, CE, or industry-specific standards.

- Creating a design that can be assembled and tested efficiently on a mass-production line.

A frequent pitfall is the attempt to move a prototype directly to mass production. Prototypes are not engineered to withstand environmental stress, meet regulatory emissions standards, or be manufactured economically at scale. The insights gained from prototyping must inform a separate, rigorous production design process.

Navigating the complexities of IoT development requires a partner with deep experience across hardware, firmware, and software. At Sheridan Technologies, our Dynamic Expert Network provides the precise engineering talent you need to move from concept to production with confidence.

If you’re facing an IoT challenge or need to de-risk your project, schedule a brief, no-obligation consultation to discuss your requirements. Find out how we can help at https://sheridantech.io.