Firmware is the invisible, high-stakes code that makes hardware work, but getting it wrong can sink a product. A subtle timing bug, a missed security patch, or an inefficient driver can lead to costly recalls, catastrophic field failures, and blown market windows. For engineering leaders, managing firmware risk is non-negotiable—it's a direct driver of cost, timeline, and product quality.

This guide is for the VPs of Engineering, CTOs, and program managers responsible for shipping complex electronics on tight schedules. It’s for operators who know the pain of a chaotic board bring-up or a late-stage integration nightmare. This is not for hobbyists or low-stakes projects where a full system reset is an acceptable fix.

We’ll frame the core decisions around leveraging external firmware development services to de-risk your program and accelerate your timeline. By the end, you'll have a clear framework to:

- Structure a firmware lifecycle that moves predictably from prototype to production.

- Identify the failure modes that typically derail firmware projects and how to spot them early.

- Evaluate a firmware partner's true capabilities, separating real engineering discipline from a slick sales pitch.

What Do Firmware Development Services Actually Deliver?

Firmware development is more than just writing code; it's a specialized discipline that bridges the gap between raw silicon and functional software. Misunderstanding the scope of firmware development services is a primary cause of stalled projects, as misaligned expectations between hardware, firmware, and application teams create friction and rework. A well-defined scope is the first line of defense against scope creep and integration failures.

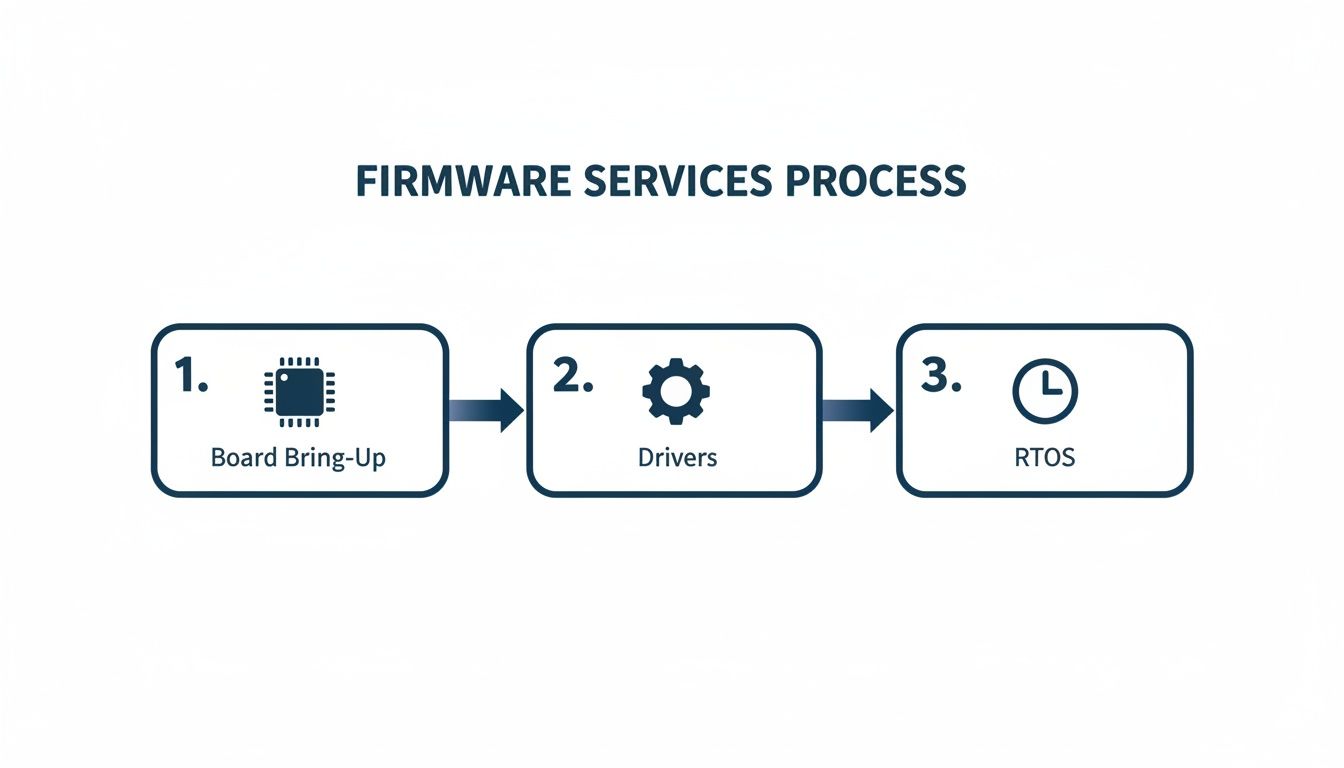

The process almost always begins with board bring-up: the methodical process of powering on a new PCB for the first time. This isn’t a simple flip of a switch. It’s a rigorous, step-by-step verification of the hardware fundamentals: Are power rails stable and within tolerance? Are clock signals clean? Can the CPU fetch its first instructions from flash? This foundational phase transforms a piece of fiberglass into a testable system, unblocking all subsequent development.

Core Development Layers and Their Purpose

Once the hardware is confirmed alive, development moves up the stack, creating the software layers that control its functions.

- Peripheral Drivers: This is low-level code that directly manipulates hardware components like sensors, memory chips, and communication buses (I2C, SPI, UART). A poorly written driver can create system-wide instability or performance bottlenecks.

- Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL): A well-designed HAL creates a clean, consistent API that decouples the main application from the specific hardware implementation. This is a critical strategic asset; it allows the firmware to be ported to a new PCB with a different microcontroller, drastically reducing the cost and timeline of future product revisions.

- Bootloaders: As the first code to execute on power-up, a robust bootloader is essential for managing application updates, performing self-diagnostics, and enabling secure Over-the-Air (OTA) updates.

The market reflects this need for specialized expertise. The global firmware engineering service market is projected to grow at a CAGR of 5.8% from 2025 to 2031, driven by industries that cannot tolerate failure. Significantly, testing and verification services account for over 40% of this market—a clear signal that quality assurance and risk reduction are the primary value drivers. You can dig into the full market analysis on lucintel.com to see these trends.

One of the most common—and costly—mistakes we see is treating firmware as an afterthought to hardware design. High-performing teams involve firmware engineers during schematic capture. This ensures the design includes necessary debug ports and test points, making the board testable from day one and avoiding painful hardware spins.

How Firmware Services Drive Business Outcomes

Connecting firmware activities to business impact is crucial for making smart resource allocation decisions. The table below outlines key service areas and their direct influence on program success.

| Service Area | Key Activities & Deliverables | Primary Business Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Board Bring-Up & Diagnostics | Initializing hardware, verifying power/clocks, debugging boot process. Deliverable: Stable, testable hardware platform. | Time-to-Market Acceleration: Quickly validates hardware, enabling parallel software development and reducing early-stage schedule risk. |

| Driver & HAL Development | Writing peripheral drivers, creating a hardware abstraction layer. Deliverable: Documented, reusable HAL. | Reduced Total Cost of Ownership: A modular HAL enables easier porting to new hardware, lowering long-term development costs for product iterations. |

| RTOS Integration | Selecting, configuring, and optimizing a real-time operating system. Deliverable: Deterministic task scheduling. | Enhanced Reliability & Performance: Guarantees predictable timing for mission-critical applications (medical, industrial, automotive), meeting safety and performance requirements. |

| Bootloader & OTA Updates | Developing secure bootloaders and robust Over-the-Air update mechanisms. Deliverable: Secure, fail-safe update client. | Improved Product Lifecycle & Security: Allows for secure remote feature updates and bug fixes, eliminating recall costs and enhancing customer satisfaction. |

| Firmware Optimization | Optimizing code for speed, memory footprint, and power consumption. Deliverable: Power/performance benchmarks. | Lower BOM Cost & Better UX: Enables responsive performance on less expensive hardware and extends battery life for portable devices. |

| Verification & Validation | Unit/integration/HIL testing, manufacturing test hooks. Deliverable: Test plan, coverage report, release criteria. | Reduced Field Failures & Brand Risk: Systematically finds bugs before shipment, preventing costly recalls and protecting brand reputation. |

| BSP Development | Creating a complete Board Support Package with drivers and libraries. Deliverable: Turn-key development environment. | Increased Development Velocity: Provides a stable foundation for application developers, dramatically accelerating the overall software schedule. |

Ultimately, a strategic approach to firmware development builds a reliable and maintainable foundation that directly supports business goals, giving your product a competitive advantage.

Key Firmware Specializations

- Real-Time Operating System (RTOS) Integration: For systems requiring deterministic timing (robotics, industrial controls, medical devices), an RTOS is essential. This service involves selecting and tuning an RTOS like FreeRTOS or Zephyr to manage tasks and guarantee that critical operations meet their deadlines without fail.

- Board Support Package (BSP) Development: A BSP is a complete software package tailored to a custom board. It includes all necessary drivers, bootloaders, and toolchains, providing a turn-key solution that allows application developers to be productive immediately without needing deep hardware knowledge.

Structuring the Firmware Development Lifecycle

Winging it in firmware development is a recipe for disaster. A structured lifecycle isn't bureaucratic overhead; it's the only proven way to manage complexity, mitigate risk, and deliver a reliable product on a predictable schedule. It provides clear gates and deliverables, transforming an unpredictable art into a repeatable engineering discipline.

Phase 1: Discovery and Architectural Strategy

This phase occurs before a single line of code is written. It translates business goals into concrete engineering requirements. Rushing discovery is the leading cause of late-stage failures and costly rework.

Key deliverables from this phase must include:

- System Requirements Document (SRD): The source of truth for the project. It defines performance targets (e.g., boot time <500ms), power constraints (e.g., sleep current <10μA), environmental conditions, and regulatory standards.

- Architectural Decision Log (ADL): This document captures not just what decisions were made (e.g., choice of MCU, RTOS vs. bare-metal), but why. It records the trade-offs considered, providing critical context for future development and debugging. This is a hallmark of high-performing engineering teams.

Solid documentation in SDLC is not a chore; it's a risk management tool.

The firmware architecture itself follows a logical progression, with each layer building on the one below.

This layered approach ensures that the application logic is built on a stable, validated foundation.

Phase 2: Development and Integration

With a clear architecture, development begins. This phase is about disciplined execution, not just feature creation. The goal is to build a resilient system designed for real-world conditions. This requires adherence to coding standards (e.g., MISRA C for safety-critical systems) and building in reliability patterns from the start.

A watchdog timer isn't an optional feature; it's a fundamental reliability pattern. It's a hardware-based mechanism that provides a last-resort recovery from a catastrophic software lock-up—an essential safeguard for any unattended device.

Phase 3: Verification and Validation (V&V)

The V&V phase proves the firmware meets requirements and is free of critical defects. This is not a final step but a continuous process that runs in parallel with development.

A mature V&V strategy includes:

- Unit Testing: Each software module is tested in isolation to catch bugs at their source, where they are cheapest to fix.

- Integration Testing: Modules are combined to verify their interfaces and ensure they function correctly as a subsystem.

- Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Testing: The firmware runs on the target hardware, which is connected to a simulator that mimics the real world. HIL enables automated, repeatable testing of complex scenarios that are impractical or dangerous to replicate manually. For a deeper dive, see our guide on how to test a printed circuit board.

Phase 4: Manufacturing and Deployment Readiness

This phase ensures the firmware can be reliably and securely programmed onto millions of units in a factory setting. It involves designing manufacturing test hooks into the firmware from the beginning, allowing automated equipment to program devices and run functional tests. Furthermore, a secure and robust Over-the-Air (OTA) update mechanism is non-negotiable for connected devices. It must include safeguards like cryptographic signing and rollback capabilities to prevent bricking devices in the field, which would trigger a catastrophic product recall.

Security and Reliability in High-Stakes Industries

For medical, aerospace, and industrial automation, firmware is the foundation of safety and operational integrity. In these domains, failure can have catastrophic consequences, from massive financial loss to loss of life. Firmware development services for these sectors are governed by a different standard of rigor, focused on security, reliability, and regulatory compliance.

Security begins at the hardware level with secure boot and firmware signing. These cryptographic mechanisms create a chain of trust from the moment of power-on, verifying that every piece of code—from bootloader to application—is authentic and untampered. This is the primary defense against malware and unauthorized modification. The market's focus on this is clear, with the Secure Boot and Firmware Security Market projected to reach USD 4.35 billion by 2030, driven by real-world threats and regulatory pressure.

Fault Containment and Functional Safety

High-reliability firmware must be architected to handle internal faults gracefully. Fault containment strategies are designed to isolate failures to a single module, preventing a minor glitch from bringing down the entire system. This is a core principle of functional safety standards like IEC 61508 (industrial) and ISO 26262 (automotive).

Consider a medical infusion pump where a timing error could be fatal. A robust design incorporates multiple layers of protection:

- Watchdog Timers: A hardware timer that acts as a fail-safe. If the software freezes, the watchdog resets the system to a known-good state.

- Redundant Computations: Critical calculations (e.g., dosage rates) are performed by separate tasks or cores, with results constantly cross-checked to detect discrepancies.

- Safe States: Upon detecting a non-recoverable error, the firmware transitions the device into a predefined safe state, such as halting the infusion and sounding an alarm.

A key tenet of high-reliability design is to assume that failures will happen. The system's architecture must be robust enough to detect, contain, and recover from these events without compromising the safety of the operator or the integrity of the mission.

Choosing the right reliability patterns involves critical architectural trade-offs between cost, complexity, and acceptable risk.

Firmware Reliability Patterns: A Trade-off Analysis

| Reliability Pattern | Primary Failure Mode Addressed | Implementation Trade-offs | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watchdog Timer | Software hangs, infinite loops | Simple to implement; low overhead. Recovery is abrupt (system reset), which may cause data loss if not managed. | General system responsiveness and recovery from total lock-ups in most embedded systems. |

| Dual-Core Lockstep | Hardware faults, transient errors (SEUs) | High hardware cost and complexity. Provides excellent error detection but not inherent correction. | Safety-critical applications (e.g., automotive braking, flight controls) where deterministic error detection is paramount. |

| Error-Correcting Code (ECC) Memory | Data corruption in RAM/Flash | Adds small hardware overhead. Corrects single-bit errors transparently but cannot handle multi-bit corruptions. | Systems where data integrity is critical, especially in high-radiation environments (e.g., aerospace, high-altitude). |

| Software Redundancy (N-version) | Software bugs, algorithm flaws | Extremely high development cost (requires independent teams); complicates testing and synchronization. | The highest-stakes systems (e.g., avionics) where the cost of failure justifies massive development overhead. |

Navigating Regulatory Compliance

In regulated industries, compliance is not an optional add-on; it must be designed in from the start. For medical devices, IEC 62304 governs the software lifecycle, demanding rigorous documentation, risk management, and full traceability. For aerospace, DO-178C imposes even more stringent verification requirements. Best practices for securing IoT devices are also increasingly relevant across all high-stakes connected products.

Achieving compliance readiness means generating the evidence—the "paper trail"—that proves due diligence at every step, including requirements, architecture specs, verification plans, and test results. For more on this, see our guide on security in embedded systems.

How to Select the Right Firmware Development Partner

Choosing a firmware partner is a critical decision that directly impacts product risk and time-to-market. The right partner accelerates your timeline; the wrong one introduces chaos, delays, and technical debt that can plague a product for its entire lifecycle. The evaluation process should focus on identifying signals of engineering discipline, domain expertise, and a proven process for navigating the path from prototype to production.

Evaluating Technical Acumen and Domain Experience

The most important filter is relevant experience in your industry. The skills required for consumer IoT are fundamentally different from the rigor needed for medical devices. Look for evidence that a potential partner understands the specific physics, failure modes, and regulatory landscape of your market.

Ask targeted questions to gauge their depth:

- For medical devices: “Describe your approach to risk management under ISO 14971 and how that flows into your V&V strategy for an IEC 62304 Class C device.”

- For industrial controls: “How do you approach designing a system to meet a specific Safety Integrity Level (SIL)? Walk me through the trade-offs between hardware and software redundancy.”

- For connected devices: “Detail your strategy for a secure and robust OTA update mechanism. What specific measures do you take to prevent bricking devices and ensure rollback capability?”

Listen for specific references to standards, tools, and past projects. Vague answers are a major red flag.

Assessing Engineering Process and Discipline

A partner's development process is a direct predictor of project success. Strong engineering discipline is what prevents projects from descending into chaos.

The surest sign of a high-performing engineering team is their obsession with documentation and verification. They don’t see it as overhead. They see it as the only way to manage complexity and kill risks before they blow up late in the game.

Probe their operational maturity with these questions:

- EVT → DVT Transition: “How do you manage the transition from EVT to DVT? Describe your process for design freeze and Engineering Change Order (ECO) control.” A mature answer will cover formal change control, regression testing, and clear communication loops.

- Root-Cause Analysis: “An intermittent bug appears during system testing. Walk me through your diagnostic process.” Look for a methodical approach involving instrumentation, logging, and tight collaboration between hardware and firmware teams.

- Release Artifacts: “What documentation is included in a final firmware release package?” Beyond source code, a professional team will deliver release notes, test plans, coverage reports, and architectural diagrams.

The need for a secure firmware supply chain is another critical differentiator. The Firmware Signing Platform Market is projected to double from USD 1.4 billion in 2025 to USD 2.84 billion by 2029. A 2024 Pentagon report found that 40% of breaches in UAV sensors were due to unsigned code. A partner not fluent in secure boot and firmware signing is unprepared for modern product development. You can explore the market drivers on Research and Markets.

Aligning on Engagement and Business Models

The engagement model must align with your project's needs and risk profile. Each model has distinct trade-offs.

| Engagement Model | Best For | Key Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Time & Materials (T&M) | Projects with evolving requirements or significant R&D risk. | Pros: Maximum flexibility to pivot. Cons: Budget is variable and demands strong project management oversight from you. |

| Fixed-Price | Projects with well-defined, stable requirements. | Pros: Predictable budget. Cons: Inflexible; any change often means a costly and friction-filled change order. |

| Dedicated Team / Retainer | Long-term products needing ongoing development and support. | Pros: Deep team integration and knowledge retention. Cons: Higher long-term cost; less efficient for short, specific tasks. |

Choosing the right model is a strategic decision. For de-risking new technology, T&M offers necessary flexibility. For a well-understood product, fixed-price may be suitable. A true partner will help you select the model that best aligns with your goals. As a full-stack product development firm, Sheridan Technologies offers integrated models designed to eliminate handoffs and accelerate the entire prototype-to-production journey.

Diagnosing And Recovering A Failing Firmware Project

Even well-planned firmware projects can veer off course. When schedules slip, budgets inflate, and the hardware remains unstable, the project is in distress. For a technical leader, a failing firmware program is a critical threat that can jeopardize an entire product launch.

These failures are rarely sudden; they are the result of escalating issues that snowball over time. The key is to recognize the early warning signs and execute a structured recovery plan before the project becomes unsalvageable.

Recognizing The Symptoms Of A Project In Distress

A firmware project in trouble often exhibits a set of classic symptoms. Identifying these early is critical.

- The Board Won't Come Up: Weeks into the project, the team is still struggling with the initial board bring-up. This points to fundamental hardware issues, incorrect component selection, or a critical gap between the hardware and firmware teams.

- "Ghost" Bugs: The system is plagued by intermittent, non-reproducible bugs. This is a classic indicator of deep-seated issues like race conditions, memory corruption, or hardware-level signal integrity problems.

- Bug Regression: During DVT, every bug fix introduces two new, unrelated bugs. This "whack-a-mole" scenario signals a breakdown in version control and a lack of disciplined regression testing.

- The Blame Game: The hardware team blames the firmware, and the firmware team blames the hardware. This indicates a failure of system-level ownership, with no single person responsible for driving cross-functional issues to resolution.

A project that is perpetually "90% done" is a project in serious trouble. This symptom often masks a deep architectural flaw or a complete underestimation of the final, painstaking integration and validation effort required to ship a reliable product.

Triage and Recovery: A Step-by-Step Playbook

Once a problem is identified, decisive action is required. The goal is not to assign blame but to stabilize the project and establish a clear path forward through a structured triage process.

Step 1: Halt And Assess

Call an immediate timeout on all non-essential development. Continuing to write code on an unstable foundation only compounds the problem. Convene the key technical leads (hardware, firmware, systems) for a no-blame assessment to create an honest inventory of the project's state: What works? What is broken? What are the biggest unknowns?

Step 2: Instrument Everything

You cannot fix what you cannot measure. The immediate priority is to instrument the firmware with robust logging and telemetry to make the system observable.

- Implement a lightweight logging framework to output system state, error codes, and key variables over a debug interface like UART.

- Use a logic analyzer to correlate software events with hardware signals. This is often the only way to diagnose timing-related bugs.

- Add dedicated manufacturing test hooks to the firmware to allow for exercising specific hardware blocks in isolation, which is invaluable for root-cause analysis.

This data-driven approach moves the team from guesswork to evidence-based debugging.

Step 3: Re-baseline and Execute

With a clearer understanding of the issues, create a realistic recovery plan. The original schedule is irrelevant. Build a new plan based on tangible milestones.

Create a risk burn-down chart that lists the top 5-10 technical risks. Assign a single owner to each risk and define clear, measurable criteria for its resolution. This enforces accountability and provides a visible measure of progress. Re-baseline the project schedule around these key milestones to provide leadership with a credible new timeline and give the engineering team achievable short-term goals.

Getting From Here to Production-Ready Firmware

Translating theory into action is what separates a successful product launch from a stalled one. The goal is to take deliberate steps to de-risk your program and build momentum, starting Monday morning.

Run a Quick, Honest Process Audit

Begin with a candid assessment of your current firmware development process. You cannot fix what you don't acknowledge.

- Documentation: Do you have a formal SRD? Crucially, do you maintain an Architectural Decision Log that explains why key technical choices were made?

- Testability: Is your firmware designed for test? Does it include logging, telemetry, and manufacturing test hooks? If not, you are flying blind.

- Handoffs: Where does friction occur? Identify the points where communication breaks down or ownership becomes ambiguous between hardware, firmware, and software teams.

Prepare to Engage a Partner

If you are considering engaging firmware development services, your preparation will determine the engagement's success. A partner can only be as effective as the information you provide. Compile a concise package detailing your project's current state, known challenges, and definition of success.

High-performing teams don't wait for problems to show up during the eleventh hour. They proactively design for manufacturability and testability from day one. This single shift in mindset dramatically cuts down late-stage risk and paves a much smoother road to production.

For teams needing to accelerate their timeline or recover a project in distress, bringing in an expert partner for a targeted manufacturing readiness assessment can be a powerful next step.

Frequently Asked Questions About Firmware Development

Every technical leader faces a common set of questions when planning a firmware project. Let's address the most critical ones regarding cost, definitions, and IP protection.

How Much Do Firmware Development Services Typically Cost?

Firmware cost is a direct function of complexity and risk. A simple proof-of-concept for a non-connected device might fall in the $25,000 – $50,000 range. In contrast, production-ready firmware for a medical device requiring IEC 62304 compliance can easily exceed $300,000 due to the extensive verification, validation, and documentation required to prove safety and efficacy.

Key cost drivers include:

- System Complexity: The number of peripherals, communication protocols (e.g., Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, CAN bus), and the need for a real-time operating system (RTOS) significantly impact effort.

- Regulatory Requirements: Development for medical, aerospace, or industrial safety domains requires a rigorous, process-driven approach that substantially increases engineering hours.

- Hardware Maturity: Working with new, unproven hardware requires more time for bring-up, debugging, and integration compared to using a well-known platform.

What Is The Difference Between Firmware And Embedded Software?

While often used interchangeably, these terms have a distinct meaning for engineers, based on how tightly the code is coupled to the hardware.

Firmware is the software that is intrinsically tied to the silicon. It is the first code to run and is responsible for hardware initialization and low-level control. Bootloaders and peripheral drivers are classic examples of firmware.

Embedded software is the broader category, encompassing all software that runs on a non-PC device. This includes the firmware, as well as any higher-level operating systems, middleware, and applications that run on top of it. In short: all firmware is embedded software, but not all embedded software is firmware.

How Can I Protect My IP When Working With A Partner?

Protecting your intellectual property requires a multi-layered strategy combining robust legal agreements with secure operational practices.

It starts with the legal framework: a comprehensive Master Services Agreement (MSA) and a detailed Statement of Work (SOW) should explicitly state that all work product and resulting IP belong to you. These documents, supported by a mutual Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA), form the legal foundation of the partnership.

Operationally, your source code must be managed in secure, access-controlled repositories. A credible partner will have strict, documented processes for handling client data, ensuring your most valuable assets are protected at all times.

At Sheridan Technologies, we build transparent, high-trust partnerships focused on safeguarding your IP while accelerating your timeline. If you're looking to de-risk your next hardware project, a manufacturing readiness assessment can ensure your product is truly ready to scale.